Are the Kardashians symptoms of a vacuous, money-grubbing culture, in which every aspect of one’s life is up for scrutiny and up for sale? Or do they represent a new, female-empowered meritocracy of fame, led by social media influencers, who have risen high on audience approbation? For Ellis Cashmore, author of Kardashian Kulture, the emphasis very much tilts towards the latter. Above all, he sees Kardashian-style celebrity culture as about “change”. He tells us that Kardashian celebrity has “changed everything”, from the way we understand gender, race and sexuality and even ourselves (class gets no mention here) to disrupting and revolutionising the relations of production and consumption (and here he updates very old arguments about consumer sovereignty). When Cashmore declares “we have changed”, the “we” refers to consumers, not citizens.

I can’t help thinking that there are more probing questions to be asked. For example, much of the “change” has been with us for some time. Kim Kardashian, like those whom cultural critic Daniel Boorstin lamented in 1962 were “well known for their well-knownness”, is famous, not because of any perceived “talent”, but because she “appears”. And she appears in close-up, sating a presumed desire for “intimacy”. Yet this is not a new “noughties” form of fame. As many film scholars will tell you, the close-up has long produced a sense of intimacy between audience and star, and this was a public desire that was created rather than innate.

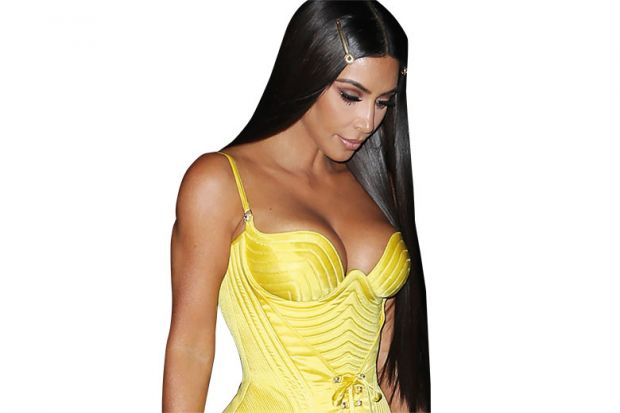

What is also not new is Kardashian making big bucks from “flaunting” her sexuality – the public female body has been gendered in this way for a long time. Rehearsing the feminist debates around postfeminism, Cashmore asks if she is complicit in the continuing reduction of women’s value to sex. Or is she a gender-rule-breaking, postfeminist icon who, standing on the shoulders of Madonna, courts scandal by exposing herself of her own free will, and thereby takes “ownership” of her sexuality and body? Again, he comes down on the latter side – she is an example “playing others who think they are playing you”. Here Cashmore is engaging in “commodity feminism”, a term coined by Rosalind Gill to explain how feminism can be appropriated for commercial purposes and emptied of political significance. Kardashian’s naked and sexualised appearances are not “breaking taboos”; women have long been expected to be excessive, narcissistic, to perform sexiness and to be sexually available, but in ways designed for male pleasure and tied to male power, as #MeToo has shown. Anyway, women’s oppression isn’t just about male sexism. Sexism is a function of wider structural control of the female body and, particularly, female reproduction, thus the cultural insistence that woman-is-body that Kardashian celebrity plays into.

Kim Kardashian does not upset cultural expectations; what is new are claims about sexualised female performances, which confuse monetising them with wider female empowerment even while patriarchal power relations remain intact. Cashmore pities anyone foolish enough to dream of something better – they are, he claims, like the Indigenous Americans in the 19th century who performed Ghost Dances to drive white people away, doomed to failure. In reality, the fact that First Nation resistance persists two centuries on provides hope for us all. If we don’t draw a halt to our celebrity-fuelled unsustainable consumerism, we are all doomed. Ghost Dancers of the world, unite.

Milly Williamson teaches in the department of media communications and cultural studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is the author of Celebrity: Capitalism and the Making of Fame (2016).

Kardashian Kulture: How Celebrities Changed Life in the 21st Century

By Ellis Cashmore

Emerald Books, 224pp, £14.99

ISBN 9781787437074

Published 22 March 2019