“We need to allow researchers to use their skills and assessment of a situation to take calculated risks.”

This is the view of Ruben Andersson, whose new book, No Go World: How Fear Is Redrawing Our Maps and Infecting Our Politics, features some “adventurous” research in Ethiopia and Senegal, on the US-Mexican border and even at the migrant “welcoming centre” on the Italian-owned Mediterranean island of Lampedusa – where we find the associate professor of migration and development at the University of Oxford “cursing [him]self for walking in flip-flops” as he steps on “rusty old barbed wire marking the edge of the military zone”.

Andersson has long been an intrepid traveller. His first book, Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe, published in 2014, describes “setting out as a young man in the late 1990s on the one-time overland hippie trail to Asia from my suburban Swedish home, hitchhiking with a tiny backpack, a bit of money, and a piece of cardboard saying ‘India’ held up to passing cars”.

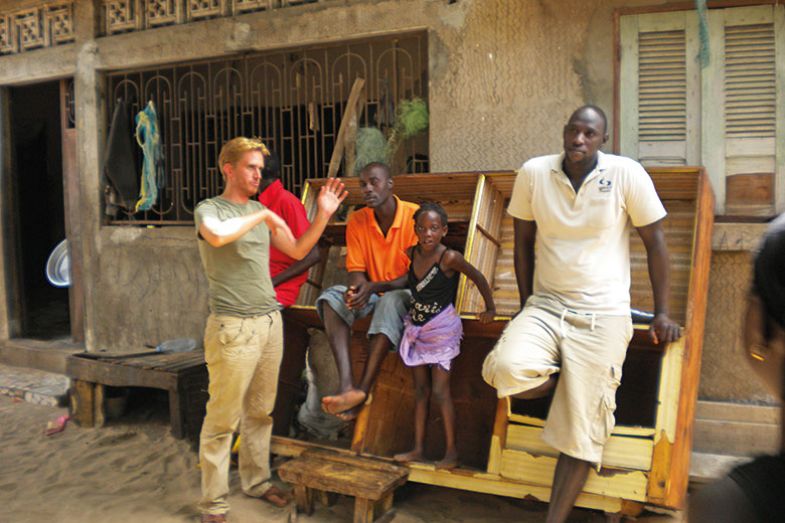

Something of the same spirit initially spurred Andersson’s research. Part of the appeal of becoming an anthropologist, he tells Times Higher Education, is “the idea of going to far-flung places and sharing a way of life very different to our own”. When he began studying undocumented African migrants trying to reach Europe, therefore, he hoped to “follow people on their journeys and really understand them from the inside: what it is like to cross these borders in the middle of the night, skirt a border control or a fence, trundle across the Sahara in a truck and so on”.

What Andersson soon realised, though, was that he had a somewhat romanticised, tourist’s-eye view of the “adventure” of crossing the Sahara. But he also realised that he was far from alone in his fascination with migrants. To their frequent irritation, they were “showered with attention from researchers, academics, journalists, policy makers and NGOs”. So he abandoned thoughts of getting to the heart of the migrant experience and began instead to explore what all this attention is “telling us about how we deal with migration and the politics of migration”.

As Andersson reflected on this while carrying out fieldwork from West Africa through the Maghreb to southern Spain, Illegality, Inc. became a book about what he now calls “the early stage of the border control industry”. This, in turn, laid the foundations for today’s “militarised, security-based border control, based around building fences and [staging] crackdowns in African countries, in collaboration with richer nations, [incorporating] extensive surveillance and drones, satellites, radar and so on”.

Such an approach, in Andersson’s view, is hopelessly counterproductive. As he puts it in No Go World, published this month, “Europe’s fight against unauthorized migration has created more chaos as fatalities rise and smuggling networks grow stronger with each new punitive measure – which in turn justifies reinforcing the border security industry that helped cause the chaos in the first place”. Although he had some modest success in his attempts to get this message across to the media around the time Illegality, Inc. was published, the 2015 refugee crisis means that “the door is now slammed shut: the trajectory Europe was already on has now consolidated”. And that, he believes, is very bad news for us all.

For all the adventurous fieldwork that went into it, No Go World shares Illegality, Inc.’s themes of unintended consequences and not quite getting to the heart of the action. Mali is a case in point. Andersson has often visited the country, which was “long seen as a stable outpost in West Africa, a donor darling”. But then came the outbreak of fighting in 2012, which led to French military involvement the following year and news reports portraying Mali as “a hotbed for jihadis and state failure”.

In early 2014, Andersson began work on a new project about remote Western interventions, which eventually became No Go World. Although he knew he would never get clearance to visit war-torn northern Mali, he was still keen to visit places such as the military training camp in Koulikoro, a city 60 km from the capital, Bamako, in the country’s south-west. But his then employer, the London School of Economics, “put [him] in touch with security officers, the security company and so forth, and we ended up having an extensive discussion about insurance premiums in relation to research budgets”, Andersson explains. “The ‘special risk premium’ was £1,000, reduced to £750 (already at the budget limit for me) if I didn’t leave the capital.”

Although initially he found it “very frustrating” to be confined in this way, what Andersson soon realised was that “everyone else was facing the same dilemma”. Bamako was full of “peacekeepers hiding behind bunkers” and “aid workers working at a remove from the field”, so his research and book became focused on “powerful actors taking a keen interest in these far-flung danger zones but not being able to enter them and fully engage with local society. Bamako was the story.”

Thus, as Andersson explains in the introduction, No Go World is largely about “the obstacle to going there…Instead of donning the proverbial khakis and pith helmet of my anthropological ancestors, returning heroically with my ethnographic heist, I shifted my gaze toward the distancing at work in the relationship between interveners and the intervened upon.”

A central issue of the book is how we map the world. Afghanistan was once on the hippy trail. Not so long ago, northern Mali’s Timbuktu – traditionally the symbol of ultimate remoteness for Europeans – was served by direct budget flights from Paris. Now, however, the whole region, from the Sahara and the Sahel through the Horn of Africa to Afghanistan, has been reimagined as what one British diplomat jokily called “a banana of badness”. An American article memorably referred to the Sahara as a “swamp” that needed to be drained.

As No Go World reminds us, this new sense of a globe divided between “an enlightened liberal order” and barbarous no-go areas full of terrorists, jihadis and smugglers echoes the medieval maps that depict a Christian world of light contrasted with monsters and dragons skulking round the edges. It may, Andersson suggests, reflect a political or psychological need for new enemies after the end of the Cold War. But he doubts the wisdom of all the “employers, newspapers, insurance companies, and travel advice-wielding foreign ministries” that depict vast regions as “rife with danger”.

Among those dangers is the “perpetual emergency” of migration, Andersson points out. But “by framing migration as an existential threat, we are also emboldening ‘partners’ on the other side to use it for leverage”, he warns. Colonel Gaddafi, for instance, ended international sanctions against Libya by threatening to unleash the many migrants in his country. In 2010, he even warned that Europe would “turn black” if the European Union didn’t provide significant financial support for his regime. Other repressive African governments have played the same card, particularly after seeing the vast amounts of European money promised to Turkey in 2015 for agreeing to shut down the flow of Syrian refugees. On a much smaller scale, No Go World tells the story of a young man in Bamako who contemplates taking a Western hostage and “mobilizing a menace to get money and attention”. When the main international asset of such people is no longer their “development potential” but the danger they represent, it is hardly surprising if they try to cash in on this, Andersson says.

Western efforts to keep the supposed dangers posed by migrants from their own shores are manifested not merely in bribes to foreign governments but also in arm’s-length military intervention, via drones, air strikes and African surrogates. But while such tactics avoid putting Western soldiers and aid workers at risk, the lack of any real engagement with the local population means that it is unlikely to be very effective and can often prove counterproductive, Andersson believes.

He is scathing, for instance, of the UK and France’s intervention in Libya’s civil war in 2011, launching airstrikes that ultimately culminated in Gaddafi’s overthrow and murky death: “Going into Libya without a plan, with remote-control interventions, without thinking of the long-term consequences, led to fighters coming back into Mali, helping the destabilisation of that country. One type of intervention sets in motion a larger set of crises.”

Terrorist attacks in Western cities are just the most traumatic sign that dangers can’t be safely relegated to the margins of the map – especially given that they are often partly a response to Western actions, Andersson says. Moreover, while groups such as Islamic State may be “essentially a bunch of murderers”, they “thrive on heavy-handed security interventions” to gain adherents.

No Go World offers an exceptionally sobering analysis, so does Andersson have any suggestions as to how we – and academics in particular – might try to improve matters?

The conclusion of his book retreats from war zones to “the sedate lull of an Oxford college”, where he has been involved in a dispute about a ferocious fire alarm that goes off every time someone starts frying a steak. Yet, in going off at the slightest puff of smoke, it also protects managers' backs in the unlikely event that the puff signifies the start of a real fire.

Similar “economies of risk” apply in border security, we read, in which “hiding staff behind bunker walls is expedient, as it shields risk managers, bosses, and political paymasters from political, legal, and financial risk should an attack take place”.

The problem is that this tends to confine Westerners to the part of Bamako known as “Peaceland” – or the “Kabubble” in Kabul – where they are relatively safe but in effect cut off from local populations. It also obliges the local populations to run all the risks, driving a further wedge between them and their supposed Western helpers.

“We need to break that divide,” reflects Andersson, “by breaking out as civilian visitors, researchers, aid workers – even as tourists. And that means assuming some risk.” In the wake of the unsolved murder of University of Cambridge PhD student Giulio Regeni in Egypt in 2016, it is perhaps understandable that universities prefer to err on the side of caution, and Andersson acknowledges that “there are risks out there”. But he is concerned that what he sees as increasingly excessive risk aversion could have a debilitating effect on research and, consequently, on understanding.

“We do need to breach those barriers and engage in various ways,” he says. “And it’s becoming increasingly difficult.”

Ruben Andersson’s No Go World: How Fear Is Redrawing Our Maps and Infecting Our Politics was recently published by the University of California Press.

后记

Print headline: Risky business