This is a book on the (very large) subject of “the Enlightenment” and its moral consequences. That it is a traditional scholarly work can be judged from the fact that only 250 of its 386 pages are text, while the remaining 136 are notes and appendices. The “Enlightenment” is seen as not a “project” but a “paradigm”, a complex change in mindset occurring over three centuries from the 15th onwards. Many authors are discussed, although Machiavelli, Hobbes and Adam Smith get the most attention, while discussions of happiness and its pursuit, our supposed raison d’être in the Enlightenment paradigm, feature prominently.

It is more difficult to describe the central thesis of the book. In summarising, the author says, “This book has been about power, pleasure and profit, three goods which can be pursued without limit. These endless pursuits stepped into a gap opened up by the decline of godliness and of Aristotelian virtue.” The blurb on the cover adds that this “created a world in which virtue, honor, shame and guilt count for almost nothing and what counts is success”. That is a rather more dramatic and contemporary claim, suggestive of a kind of moral degeneracy. I don’t think that David Wootton is generally trying to justify that kind of claim, although he gets fairly close if you put his account of Smith’s non-interventionist attitude to famine together with his statement that Smith’s thought has a “grip” on our culture. (He would be far from the first author I have reviewed or interviewed who has been given a publisher’s puff that goes beyond his real claims in the direction of contemporary “relevance”.)

However, there is a huge amount to enjoy and admire in the detailed argument of the book. In my case, this would certainly include the introduction to such previously unknown characters as Émilie Du Chatelet and Edmund Spenser (as a political thinker), and the complex accounts of the origins of concepts such as “the pursuit of happiness”. For instance, I was unaware of the ways in which the language of ethics seemed to change with each generation or of Smith’s “linguistic conservatism”: apparently there are only five new words in The Wealth of Nations, and those fairly trivial, making him a far from typical economist.

But I am much less convinced by the supposed general thesis of the book. In discussing the “Enlightenment”, the author seems to me to conflate true selfishness with the kind of instrumentality that aims at maximising the good of a collective that is smaller than the whole of humanity. Machiavelli, for example, said that he would give up his soul for his country: that surely makes him a good deal more altruistic (in our terms) than devoutly religious persons hoping to go to heaven?

Even more important, I don’t think that Wootton properly appreciates the wonderful negative aspects of the “Enlightenment”. To pursue the metaphor, you don’t always have to find a new source of light to be enlightened. You can sometimes just remove the obstacles between you and illumination. I think that this is particularly important in considering what Voltaire, in his thoughts on England, had to say, or Bernard Mandeville, in the various versions of The Fable of the Bees, or David Hume, particularly in his History of England. It amounts to a kind of zeitgeist that says, “We spent two centuries fighting and arguing about the related questions of religious revelation and political legitimacy. We resolved nothing, but we did learn to ignore these questions and now we are doing very well.” The Enlightenment, in this sense and at its best, is mostly about not being bothered, not about erecting ideas of equality and fraternity, because as soon as you do that you find yourself destroying wealth and (once again) chopping off heads on an industrial scale. (Mandeville went further in naughtily insisting that private vices, particularly greed, produced public virtue in the form of wealth. Greed is good, at least a lot of the time.)

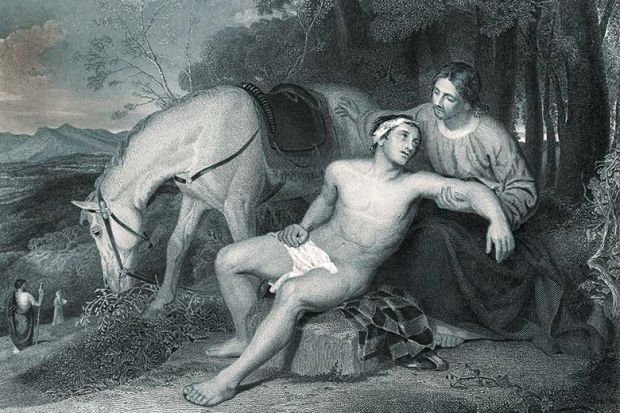

In the text, but mostly in Appendix D, Wootton considers the parable of the Good Samaritan found in Luke x, the subject of numerous pamphlets and sermons during the period that he is discussing, and irresistible as a text for clarifying certain moral questions. But I don’t think that it serves his own argument well. It is important to note that the two passers-by who ignore the mugging victim can be assumed to be religious: in the New English Bible, they are described as a “priest” and a “Levite” (a member of a tribe with specific duties within Judaism). They have, therefore, knowledge of an ethical rule book based on religion; this may, on some interpretations, keep them away from the victim because they regard him as “unclean”. In the proper and precise sense of the word, none of the three has any obligation to help; they are not, for example, doctors or married to him.

They may be thought to have a duty to help derived from some general external prescription rather than a commitment: that is a broader and more contestable term. This is what Christ seems to be suggesting because he is answering the question, “Who is my neighbour?” But in explaining the Samaritan’s motives, he describes him as being “moved to pity”, which means he is acting on emotion or ethical intuition rather than on knowledge of duty. In any case, it would be an odd kind of duty that applied only to people within our line of vision. Wootton’s account of the history of ethics offers us a long menu of general moral characteristics that might lead the Samaritan to cross the road: “benevolence”, “humanity”, “fellow-feeling”, “generosity”, “sympathy” and (from nearer our own times) “altruism” and “empathy”.

The important point is surely that the story still has complete contemporary resonance. We wouldn’t dream of saying “How medieval!” about someone who went to help a mugging victim. We can all construct contemporary versions of the narrative: in mine, the magistrate and the moral philosopher pass by, while the bloke from Wolverhampton with the tattoos and the England shirt comes over and says, “Blimey, mate, you need help.” It makes as much sense to ask why you would not help as why you would. There’s no sense in the story that helping is dangerous or even particularly costly, so wouldn’t life be more interesting and rewarding if you helped than if you did not? We may not go the whole way with Bishop Butler in equating benevolence with self-love, since it gives us pleasure, but surely they often go together like greed and good consequences.

Wootton tells us that he admires Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (1981) and is writing in the spirit of that book. When I was a teenager, I deeply admired A. J. Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic (1936) because it argued that most things people believe are “meaningless”. I came to realise (as did the author) that this was true only in terms of a particular and restricted meaning of “meaning”. In the same way, we are living after virtue only in a very particular and restricted sense of “virtue”.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick and the author of books on political theory, sport, travel and the environment.

Power, Pleasure and Profit: Insatiable Appetites from Machiavelli to Madison

By David Wootton

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 400pp, £25.95

ISBN 9780674976672

Published 26 October 2018

The author

David Wootton, anniversary professor of history at the University of York, was born in England but, he says, “spent [his] early years in Pakistan, where my parents were Christian missionaries. I have always felt somewhat deracinated as a result.” He went on to study at both Cambridge and Oxford, but “had no sense of what I really wanted to do until I read Lucien Febvre’s The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century (1942)…That got me interested in the big question of what makes modern civilisation fundamentally different from earlier civilisations, and I started work on the history of religious unbelief.”

Since then, Wootton has written a series of books about “differing aspects of the question of what we have gained and what we have lost by coming after the great revolutions that made the modern world – the printing, scientific, democratic and industrial revolutions”. Power, Pleasure, and Profit “argues that during the 18th century a vision of human nature became established according to which we are, in effect, machines seeking to maximise pleasure, and, as a means to pleasure, power and wealth. This assumption laid the foundations not only for utilitarianism, but also for modern economic theory.” It is only when we recognise the “shared assumptions” behind various forms of Enlightenment speculation that we can start to “understand why we continue, much of the time, to think along lines set down in the 18th century”.

Asked about the relevance of his findings to the current political scene, Wootton responds that his “aim is to diagnose our intellectual difficulties, not to cure them…So I am happy that different readers have appealed to the book to support radically differing solutions to our present challenges, many of which can be summed up as a crisis in liberalism. At the root of that crisis is the Enlightenment’s inadequate notion of human nature.”

Matthew Reisz

后记

Print headline: Parable of the Enlightenment