In these austere times, to be given an audience with any vice-chancellor may be considered a significant event, even for the editor of Times Higher Education. When that meeting, however, is with the long-serving leader of the globally celebrated University of Rural England – arguably the most powerful figure in these islands – the honour can scarcely be overstated.

I was visiting the university ahead of anniversary celebrations marking the series of events that changed our world forever all those years ago. Over the past few decades, a gently rising tide of achievement has brought folk of many backgrounds together here on the winter solstice to mark our common survival: an outcome due in no small part to the radical intervention of the university.

As my journey – uneventful by current standards – concluded, I was met at the frost-etched iron gates of the campus by the head porter, who, most fortunately, was expecting me and summoned the proctor. After she had completed the usual rituals to confirm that I was indeed the editor of THE, I was permitted entry and escorted across the winter-silent, ordered gardens to the Great Hall.

The proctor informed me that the vice-chancellor’s previous meeting – a routine judicial matter – had finished ahead of schedule and that my arrival was timely. I fought to suppress my sense of awe as I followed her into the presence of the great man himself.

Still wearing his magnificent robes of office, he greeted me warmly and ushered me into a side-chamber that lacked the cold austerity of the main hall. After making cursory enquiries into how the preparations for this year’s festival were progressing, I asked the vice-chancellor why he thought the festival had replaced Christmas as the most important fixture of the year in these islands.

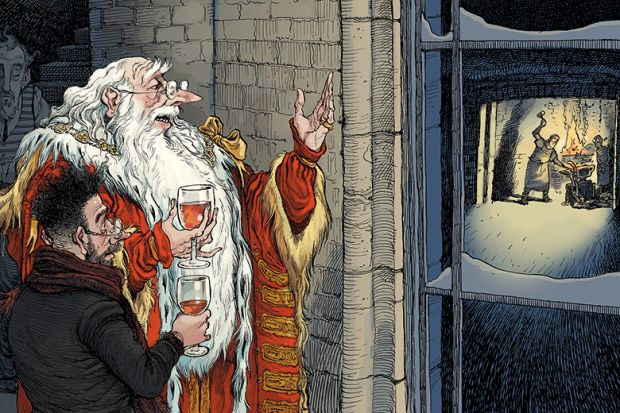

“The fact that we now date our calendar from the time of our near-destruction rather than the birth of our saviour tells you everything you need to know about how epoch-changing the Solstice Attack was,” he mused, the light of the generous wood fire dancing in the glass of excellent wine he held close to his lips. “It erupted upon an unsuspecting world at a moment that should have been devoted to peace and celebration. The midwinter festivals may even have contributed to the scale of the disaster – through the inattention of those charged with preventing such an apocalypse.”

But isn’t it almost unbearably painful to commemorate that date, on which the richness and diversity of pre-Solstice life was swept away by that obscure group of crazed maniacs, moved by some corrupt rendering of an imagined Utopia, who took it upon themselves to destroy all the old mechanisms of communication through a dire, malicious infection?

My companion gazed thoughtfully into the fire. “It is painful, truly it is. You are far too young to remember, of course: to know how it feels to see the myriad devices through which people lived so much of their lives rendered suddenly and permanently useless. To see the great web of connections that held the planet together dissolved into a shower of shattered filaments. To see, within hours, the commercial wheels that fed and warmed the planet slow to a crawl. To see, within days, the lights flicker out as power failed and darkness once again covered the Earth – broken only by the fires of panic and insurrection that raged unchecked through cities across the globe, taking countless lives with them.

“But the fewer of us that remain who actually lived through the Solstice Attack, the more important it becomes to preserve its memory, to ensure that it can never happen again – even if the emotions that its commemoration evokes are far from the communal jollity associated with the old Christmas.”

Not that the Solstice Festival is all about lugubrious memorialisation of all those who lost their lives in the chaos, of course. It is also about celebrating the central role that the University of Rural England played in sowing the seeds for recovery: a role highlighted in the vice-chancellor’s recently written book, of which more than two dozen copies have now been transcribed. The book draws on his personal experience of the Solstice Attack, which occurred when he was a junior lecturer in management studies, and I asked him to fill in some of the less familiar details of what occurred. Why, for instance, had the University of Rural England managed to hold the line while so many other universities had been looted and destroyed in the chaos?

“Through historical logic and happy accident,” he replied. “Because we’re on this isolated promontory above the river, the campus was defensible by the former servicemen who were the backbone of the portering team at the time. Resilience, loyalty and an instinct for action meant they kept the crazed hordes mostly at bay, until they ceased to be a threat. But it was the clean water from the spring within this old castle keep at the heart of our campus that proved the key to survival. Cold, fresh and unstinting, it provided a new hope to those who had none.”

The vice-chancellor adjusted his robes, evidently pleased by his turn of phrase.

“The Business School, where I worked, planned and schemed to provide a logistical response to the new reality – much aided by some handily placed warehouses. Help also came from some unexpected quarters. The amateur radio club, once the butt of some humour, ascended to prominence as the only folk who could still communicate around the world. A turbine in the river, installed long before as a foil against taxation, provided power for the limited needs of an ancient short-wave transceiver and antenna array on the roof of the physics building. Their comrades across the globe confirmed the news that the impact of the Solstice Attack was profound and universal – but the network of survivors they built up in those early days formed the hub of our new world. Even Human Resources, long the target of collective ire, finally found themselves with a role that justified their staffing and management structure, as they desperately sought to direct the work of both university staff and the wider population.”

The vice-chancellor chuckled briefly at this point, his eyes sparkling amusedly in the firelight. He was perhaps bringing to mind some formative encounter from his past – but, ever the diplomat, he declined to elaborate.

“With digital sources of information either destroyed or hopelessly moribund, the role of the university library, still home to millions of paper texts, found a new focus, too,” he went on. “The reactions of its lean remaining staff – and I mean that in both senses – to this turnaround varied from quietly gleeful to unbearably smug, but the almost carnal passion and ferocity with which the librarians guarded priceless knowledge from the depredations of those seeking to burn the books for warmth was priceless in itself.”

Pressed for more accounts of unsung heroes, the vice-chancellor mentioned the botany and agriculture departments, which oversaw the hand cultivation of crops on the former sports fields during that first summer by teams of gaunt, hungry workers drawn from the academy. A rich sense of community, he added, held the university together in those first anguished years – which grants some focus to the long-standing policy of staff support and training that still prevails today.

“Honest toil in the summer sunshine proved a tonic for those sensitive minds thought irretrievably damaged by the Solstice Attack,” the vice-chancellor added. “Cynics say that the realisation that the research excellence framework was gone forever was the most beneficial factor to morale, but the most insightful long-term contribution to academic well-being, in my view, was the expansion of the orchards and the planting of a vineyard on the south-facing slopes a few years later, allowing us to make alcoholic beverages for these special occasions.”

I was pleased to toast this certainty with the university’s celebrated merlot – after which an assistant quietly refilled our glasses.

“As the years passed and I rose into senior management, the university increasingly became the focus of regional regeneration – with a degree of outreach and community involvement that would have drawn lavish praise from many pre-Solstice commentators. The engineering department had set aside its dreams of nanotechnology and reverted enthusiastically to the business of basic manufacturing, using simple, analogue systems. We will long remember the celebrations at the opening of the iron smelter and foundry on the site of the former Computing Centre – which, being only half-heartedly defended by the porters, had been burned to the ground by an angry mob in that desperate first winter. And, of course, it led to a welcome population spike the following year.”

Once again, a smile of reminiscence flashed briefly across the vice-chancellor’s face – yet his pride in this highly regarded new facility is clear, and with good reason.

“Among their more sophisticated accomplishments has been the production of optical fibres, made with the pure quartz sand from the shoal waters of the river. We hope this will lead to the creation of a new communications network to augment, and perhaps replace, those teams of horseback couriers who currently cross the country at such great peril to themselves. If these brave souls were retrained in Morse code, by the way, they could enable new high-bandwidth communications systems, with speeds of up to 40 words per minute.”

These developments, giving hope for the rise of a new technological age, could restore our means of communication to where we were little more than a century ago. Buoyed by the wine, I ventured to remark that it would be tremendous news for civilisation if this new communications network allowed THE to reconnect with its enormous pre-Solstice audience. But the vice-chancellor appeared not to hear me. Instead, he guided me to the window of the chamber. Through the thick snow now falling on the wide stone courtyard, he pointed out the director of finance and a well-muscled clerk ceremonially hammering a heavy metallic link into the blockchain that records the financial commitments of the organisation.

“That embodiment of structure and order sums up much of what the University of Rural England stands for today,” he said with evident pride, the vivid sparks flashing in the clerk’s glasses as the joint was forged. “We rank officially as having the lowest mortality rate of any university in the country, and we are on course to see births overtake deaths within five years. Yet much remains to be done. We still haven’t settled on a new social structure for the post-Solstice world, for instance. Over the years, the best minds of our political science department have sat where we are now and argued about it, but their failure to agree on, well, anything very much, leads me to conclude that pragmatism must hold sway. Nation states and organised religion have had their day and must be supplanted. Here, in this university, we hold knowledge, wisdom and the means of both survival and development.

He stared at the scene for a moment longer, before portentously adding: “We must seize the initiative before less worthy powers can intervene.”

At this point, an aide signalled discreetly to the vice-chancellor and my audience with him – more generous than I had any right to expect – came to an end.

The following afternoon, as dusk fell over the frozen ponds of the Quad, the invited delegates for the festival and their retinues – including those who had spent weeks travelling from remote academic fastnesses across Europe at great danger to themselves – gathered in the now sumptuously decorated Great Hall.

Their bodyguards stamped the snow from their boots as the doors were closed against the mass of awestruck ordinary folk that sought to follow in their wake, barely contained by a line of staunch but perspiring porters.

The atmosphere within initially was withdrawn and circumspect, but the circulation of trays bearing the university’s apple brandy – a highly prized product of the chemistry department – quickly restored the spirits of those trodden down by the treacherous winter roads.

Exotic sweetmeats followed: delicately cooked seasonal snacks of pigeon and wildfowl, with preserved fruits gleaned from the summer harvests. Clearly, the university was seeking to impress its honoured guests, and not a few delegates took ample – even, perhaps, excessive – advantage of the munificence, enjoyed vicariously by scores of adoring faces pressed to the condensation-running glass of the Great Hall.

It was only with some difficulty – by repeatedly striking the university mace on the high table – that the proctor achieved enough order to allow the vice-chancellor to speak. Standing erect at the podium, before a tapestry emblazoned with the historic seal of the university, he presented an impressive and imposing figure. After generous words of welcome, and gracious expressions of praise to those whose journeys had incurred particular risk, he settled into his speech.

“To conclude,” he said, after a 10-minute display of logical and rhetorical skill the like of which I have rarely witnessed, “for decades we have fought without reward to bring enlightenment to this region – as others have done elsewhere. Tonight, I announce to the world that the University of Rural England will confer Fellowships on those of all stations and none.”

Faint cheers arose from beyond the windows, to which a mass of grateful ears were now pressed. The vice-chancellor smiled indulgently, the perfectly matched furs of his gown resplendent and glowing in the candlelight.

“With my family as its hereditary leaders, we will protect, educate and support our Fellows and their households – using our knowledge, influence and civil power – in exchange for a simple contribution. A mere one tenth of a Fellow’s annual crop – a tithe, one might say – will suffice to win them our protection from those ills that are in our power to defeat.”

With that, the door of the Great Hall burst open under the human pressure, and the now loudly cheering masses streamed in to prostrate themselves on the floor before their hero. Secure in the moment, the vice-chancellor strode powerfully forward to the edge of the dais and extended his heavily bejewelled hands towards them.

“It is time to rebuild our world,” he said, in emphatic, triumphant tones. “Come! Join us!”

John Gilbey is the founder of the fictional University of Rural England and worries a lot about this sort of thing. Selling the film rights to this story would have a major impact on the feasibility of his retirement plans.