The central argument made here is that the very rich in America, instead of flaunting their wealth, now consume more discreetly. Conspicuous consumption is down because flashiness is now for the lower orders. However, it may be too early to be sure if the change that Elizabeth Currid-Halkett has observed points to a new theory for a new kind of aspirational class, or something very different from what she thinks it shows.

The very rich used to buy more bling. Now they spend more on the private education of their children, on servants to make their lives easier, on healthcare and on stunningly expensive elite health insurance, and they spend a smaller proportion of their income on material goods. In making these statements, Currid-Halkett acknowledges the analysis of a mountain of consumer data carried out by her doctoral student, Hyojung Lee. She explains that the well-off believe that they are short of time and increasingly use other people’s labour to win them more time; that the (somewhat) inconspicuous consumption of education, healthcare, childcare, nannies, gardeners and housekeepers “gives people more time and, in the long run, shapes life chances”.

There is a great deal of sympathy for the rich in these pages. They are described as people who are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars that they have made “through legitimate hard work”. But their work is never described. Their “dominant ethos – working hard and acquiring knowledge” – sounds like a pastiche of Bill Gates and his earnest reading and reviewing of books. No evidence is provided that this is their actual ethos; it may be wanting to be seen to be clever, able, useful and then respected that still drives the rich. Just as we all seek respect.

The rich buy their children’s way into elite US universities. Currid-Halkett repeats the claims of others that later economic success is due to the unobserved personal characteristics of these affluent children “who attend elite universities, rather than the universities themselves”. Again, The Sum of Small Things doesn’t explain why having both access to an inherited fortune and a CV with a prestigious US college degree topping it are not the two (very large) things that give this cohort their leg up. Why else would Lee’s tables in this book show the educational expenditure of the richest 1 per cent of Americas increasing by almost 300 per cent between 1996 and 2014? That (so-called) inconspicuous consumption is hardly a small thing. And you can choose to flaunt or disguise your degree just as you flaunt or store away jewellery.

By 2014, the richest 1 per cent spent more than twice what the average member of the top 5 per cent spent on jewellery. Tragically, the lowest-income families are distinguished by disproportionately high spending on funerals. Currid-Halkett interprets this as flashily conspicuous overspending; more likely it is simply that the poor have less overall to spend and die more often. There are a lot of good data in this book, but they could often be interpreted in very different ways – especially when read from a European perspective.

The most conspicuous consumption of the richest 1 per cent peaked in 2007 and then fell rapidly with the great recession. Often it is the richest who begin a trend, from recreational opiate use in England in the 19th century through to seeing the writing on the wall and hunkering down today. As yet, while we can see many parts of this story unfolding, no one can provide an explanation that is greater than the sum of those parts. It is too early to tell what the change is, but as with so much else, a great change in consumption patterns is under way.

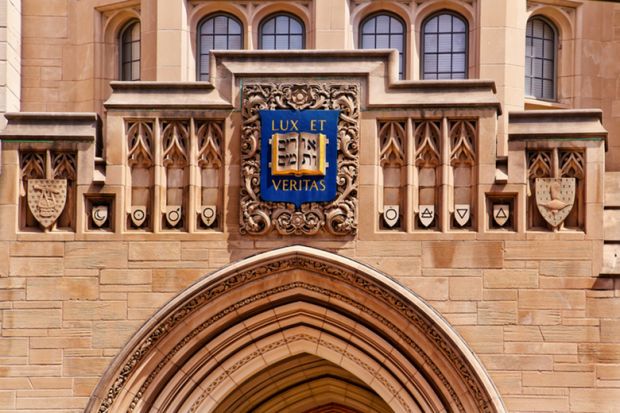

Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder professor of geography, University of Oxford. His latest book, with Dimitris Ballas and Ben Hennig, is The Human Atlas of Europe: A Continent United in Diversity (2017).

The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class

By Elizabeth Currid-Halkett

Princeton University Press, 272pp, £24.95

ISBN 9780691162737 and 9781400884698 (e-book)

Published 7 June 2017