Economic austerity has led to declines in university autonomy across Europe as governments have increased their control of institutional finances, a major study says.

Research published on 6 April by the European University Association suggests that the loss of financial autonomy in several university systems on the Continent has impacted on some institutions’ abilities to hire new staff, triggering warnings that universities’ capacities to compete internationally in terms of research and teaching are at risk.

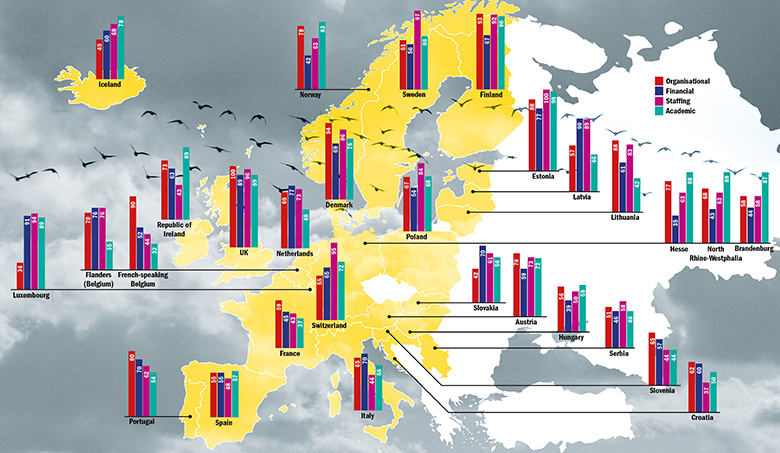

The study, University Autonomy in Europe, measured the independence of university systems in 29 countries and territories across four areas: organisational (for example, the selection of vice-chancellor and governing body), financial (such as the freedom to set tuition fees), staffing (for example, the recruitment and salaries of staff) and academic (such as recruitment of students and designing of curricula).

The research found that several countries had seen a decline in financial autonomy since the EUA’s last assessment was published in 2011.

Estonia’s score in this category declined by 13 percentage points to 77 per cent, mainly due to the abolition of tuition fees, while Hungary’s score plummeted 32 percentage points to 39 per cent, in part due to more constraints on tuition-fee levels for fee-paying students. Hungary’s universities also have reduced independence in financial matters because final decision-making powers rest with a new university chancellor position appointed by the prime minister, according to the EUA.

Thomas Estermann, the EUA’s director of governance, funding and public policy development, said that the results show budget cuts that are seen as a “temporary…reaction to the challenging economic situation” have “further impact than just the funding [of universities] for a year or two”.

Some of the countries with declining levels of financial autonomy have experienced drops in other areas of their independence.

For example, Hungary’s staffing score has also fallen, from 66 to 50 per cent. As the Republic of Ireland’s financial autonomy has fallen three percentage points to 63 per cent, its staffing score has declined by 39 percentage points to 43 per cent.

Andrew Deeks, president of University College Dublin, said that funding to Irish universities was cut by about 30 per cent during the period of economic austerity after 2008, while a cap on the number of permanent employees has led to a 20 per cent reduction in faculty and staff numbers.

During the same period, the government took control of the salaries and remuneration of staff and mandated that there would be no compulsory redundancies, he said. Despite Ireland’s economic recovery, the cuts and constraints have not been reversed.

Professor Deeks admitted that the constraints made it difficult to attract “superstar professors”, although he said that salaries were still competitive compared with UK institutions. It was also impacting on the student experience: the university’s student-to-staff ratio is now 22:1, compared with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development average of 14:1, he said.

“As the autonomy has been taken away, it has led to more inefficient use of resources and a reduction in the competitiveness of Irish universities,” Professor Deeks continued.

“The opportunities are huge. If we had the money to invest, there’s a significant number of academics both in the UK and the US who would be very willing to come to a high-quality university in Ireland – a place that will remain in the European Union, will have access to EU research funding, and is welcoming to people of all faiths and all races, something our competitors are increasingly having problems with.”

Hans de Wit, director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, said that university systems “can only really prosper if there is enough autonomy and flexibility on the financial side”.

“Of course it’s logical that there has to be some control about public funding but if it leads to much more rigid and bureaucratic systems then you create…obstacles to innovative research and innovative teaching,” he said.

Continental variation: autonomy scores for 29 European countries/territories

Source: European University Association. Note: Germany is not included and is instead represented by three German states, while Belgium is divided into Flanders and the French-speaking community

UK universities number one for autonomy in Europe

Academics in the UK enjoy more autonomy than their counterparts in other European countries, thanks to UK universities’ high levels of organisational freedom and independence when it comes to the recruitment of staff.

The country is the only territory analysed in the EUA study to achieve a top-three finish in all four areas of autonomy that were considered.

It is number one in the organisational category, which assesses freedom around the selection of the vice-chancellor and governing bodies and the capacity for institutions to decide on their academic structures, and it comes third in the other three areas.

Estonia is top when it comes to independence around staffing, which takes into account the recruitment, salaries, dismissal and promotion of staff; and academic freedom, which assesses admission procedures, degree programmes and quality assurance.

Finland and Denmark are also strong performers in several categories. Denmark, for example, has recently introduced reforms that allow universities to own their property.

Thomas Estermann, the EUA’s director of governance, funding and public policy development, said that the UK’s high levels of autonomy may be related to the fact that its universities receive the lowest proportion of funding from public sources compared with the other systems in Europe.

“If you have not that much public funding in the system, institutions should be more autonomous. There is a certain logical consequence,” he said.

At the other end of the scale, France is the worst performer on average, when all four scores are taken into account, largely due to low levels of autonomy in terms of staff salaries, student numbers, admissions procedures and degree programmes.

Meanwhile, although Luxembourg achieves the highest score for financial autonomy, it is bottom for organisational autonomy due to restrictions around selecting members of the senior management team and governing body at the University of Luxembourg.

Eastern and southern European countries generally perform poorly in the study: Serbia, Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Spain and Italy are all below the European average when the four autonomy scores are combined.

António Rendas, rector of NOVA University of Lisbon, agreed that, in general, there is more university autonomy in the northern European countries.

One factor might be that universities in southern countries tend to depend on yearly budgets, which means that long-term strategic planning is always dependent on annual changes in funding, he said.

Professor Rendas said that Portuguese universities were also subject to “tight controls” from the government between 2012 and 2015. Institutions had to apply for permission from the state before spending large amounts of money, which prevented strategic planning, and there were restrictions around the appointment and promotion of administrative and technical staff, he said.