Download: Annual tuition fee data for full-time courses at UK institutions, 2016-17

The debate over whether an undergraduate degree from an English university represents good value for money has been raging ever since the tuition fee cap was trebled to £9,000 in 2012.

After the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, however, students from the Continent are likely to face an even starker question: does a British undergraduate degree represent good value at more than £13,000 a year – or, in the case of clinical subjects, in excess of £24,000?

A survey of tuition fees for the coming academic year, compiled by The Complete University Guide and published this week by Times Higher Education, may add to fears that EU students will vote with their feet and go elsewhere post-Brexit, with significant consequences for institutions’ finances, the viability of courses and campus diversity.

“EU students currently have to be treated exactly as home students [are] in terms of fees and loans. Hence, they are treated advantageously compared to an international student paying higher fees and [ineligible for] government-funded loans,” notes David Palfreyman, director of the Oxford Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies and co-author of The Law of Higher Education. But, after the UK leaves the EU, “all that ends, except almost certainly for a transition period for students who have already started their courses prior to the triggering of Article 50 [the EU treaty mechanism by which countries can exit the bloc] – or perhaps up to the point of the Article 50 negotiations being concluded”.

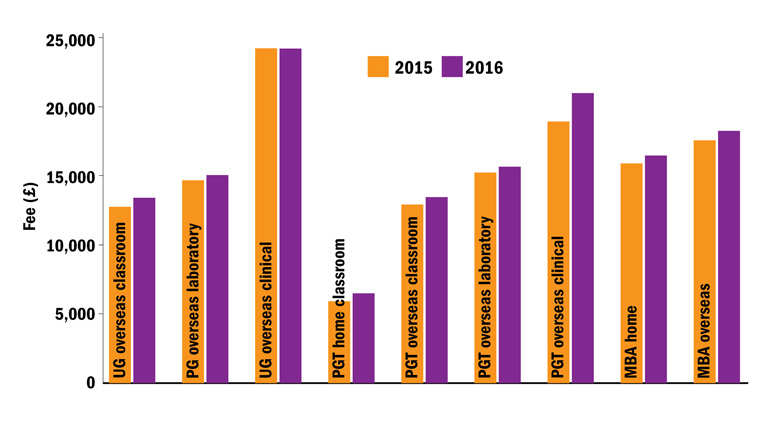

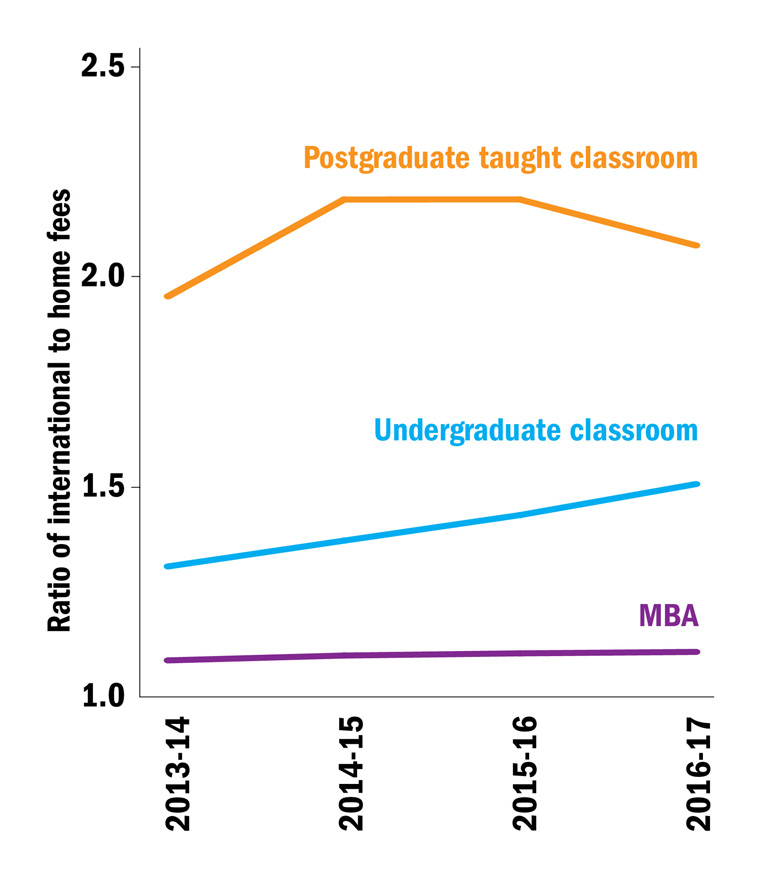

So, for the time being, EU undergraduates will continue to pay the home rate averaging just under £9,000 (rising to £9,250 in 2017‑18) to study at an English university. But, after that, they will probably be charged an international rate that, for a classroom-based course, currently stands at an average of £13,394: up 5.1 per cent year-on-year. The gap between home and international undergraduate fees has grown significantly in recent times, with the latter having risen by 18.6 per cent since 2013, while the cap means that the former has stayed largely static.

For home students, there is little difference in tuition fees between subjects, but this is another consideration that EU students may have to get used to: the average international fee for a laboratory subject now stands at £15,034 while for clinical disciplines, it is £24,169.

At taught postgraduate level, the gap between home and international fees has actually narrowed slightly this year, but the divide remains stark: the average international fee for a classroom subject, £13,442, is more than double the average home fee of £6,486. And the long-term trend is towards a widening gap, with home fees for a classroom-based subject having increased by 9.2 per cent in the past four years, compared with 16 per cent for international classroom fees. Overseas taught postgraduate students are charged even more for laboratory and clinical subjects: £15,638 and £20,956 respectively.

It is theoretically possible that continued eligibility for lower fees and, perhaps, student loans for EU students could be preserved post-Brexit in return for continued UK access to the Erasmus+ student mobility programme or EU research funding, for example. But Vincenzo Raimo, pro vice-chancellor for global engagement at the University of Reading, questions whether it would be justifiable to treat EU students differently once the UK has left the union. “The idea we would charge somebody from Italy less than somebody from Nigeria when the rules have changed just seems odd to me,” he says.

Then there is the question of what immigration controls will be applied to EU students post-Brexit. This is unlikely to be known until the negotiations with the EU have been concluded, and it has been suggested that Theresa May’s recent move from the Home Office to 10 Downing Street offers an opportunity for a fresh case to be made for all students to be taken out of net migration figures, something that she fiercely resisted when it was her direct responsibility to implement the Conservatives’ pledge to lower net migration levels to the “tens of thousands”. But subjecting EU students to the rules currently applied to non-EU learners, especially the curtailment of post-study work opportunities, would be another disincentive for them to come to the UK.

On the up: year-on-year changes to tuition fee levels

UK universities have become increasingly reliant on EU and international students as the number of domestic school-leavers has stagnated and begun to decline. Over the past five Ucas admissions cycles, the number of EU applicants to undergraduate courses in the UK increased by 25 per cent, while the total number of applicants grew by only 9.4 per cent. And, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency data, non-UK EU nationals represented 6.4 per cent of all full-time undergraduate and postgraduate students at British universities last year.

It is not a given that student recruitment from the EU will collapse, according to Dame Julia Goodfellow, chair of Universities UK and vice-chancellor of the University of Kent, which styles itself as “the UK’s European university”. “The UK is very good at getting international students: about 16 per cent of Kent’s students are international,” she says. “I think we would have a good chance of getting European students if they were charged international fees…At the moment, for international students, the pound is low, which is clearly good if you are paying in overseas currency.”

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, has argued that UK universities have “never aggressively recruited” EU students because they were included in student number controls until those were abolished last year, and he suggests that there may still therefore be untapped markets in the EU, which would mitigate any decline in recruitment. But other sector observers are less optimistic, highlighting that undergraduate tuition remains free in many EU states.

“The impact [of Brexit] can only be to reduce the number of EU undergraduate students in UK universities if they have to pay higher international fees and can’t access loans to do so,” Palfreyman argues. Compared with free continental education, “the [English] higher education brand is probably value for money, even at £9,000, especially if the [student loan] debt is unlikely ever to be paid off…But it is less value for money at international fees and probably impossible if the money has to be found upfront.”

As well as the financial loss resulting from lower recruitment from the EU, university leaders also worry about the cultural impact. Michael Arthur, president of University College London, has said that a reduction in EU recruitment would change “the very nature of a major international university in a way that is not helpful”, and Goodfellow has similar concerns.

“The biggest issue for us is that we find on open days that UK students want to come to…institutions with students from all over the world, including Europe,” she says. “They are asking us: ‘Are you sure international students will still be coming? We want to be in a diverse community.’”

Paul Wakeling, senior lecturer in the department of education at the University of York, would also regret a decline in EU student numbers “for intellectual reasons, for the [loss of] diversity of the student body and for [the increased difficulty of] attracting excellent researchers”. But he points out that, in purely financial terms, such a decline could be compensated for by the higher fees paid by those who still came. “You could halve the number of students, double the fee and still be in the same position you started with,” he notes.

Indeed, the funding gap need not be made up by EU students at all. Writing in Times Higher Education ahead of the referendum (“EU referendum: scholars weigh case for and against Brexit”, Features, 9 June), Michael Liversidge, a former dean in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Bristol, noted that EU nationals are “vastly outnumbered” in UK universities by students from further afield. “So it would not be hard for UK universities to make up the lost income from EU students by recruiting more non-EU students,” he wrote. “That fewer of them would be needed to raise the same amount could enhance the learning experience and environment for home students by easing the overcrowding.”

Home v away: price differentials

Whatever happens, it is unlikely that any volatility in recruitment would be felt evenly across the UK. Scottish universities, in particular, face significant uncertainty because the zero tuition fee means that many institutions north of the border have higher proportions of EU undergraduates than in the rest of the UK. They represent 21.2 per cent of the total undergraduate body at the University of Aberdeen, for example, and 13.5 per cent at the University of Glasgow. If EU students were required to pay international fees, those proportions could plummet. Alternatively, if their favourable treatment were preserved, Scottish institutions could see a further increase in applications from EU students who were keen on a UK degree but were unable or unwilling to pay international fees in England, Wales or Northern Ireland.

Ferdinand von Prondzynski, principal and vice-chancellor of Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, notes that continuing to exempt EU students from fees may be politically desirable “because it would place Scotland in a favourable position should, in whatever form, Scottish membership of the EU remain on the table. On the other hand, of course, it may look difficult to exempt EU students but not rest-of-UK students if Scotland is not in the EU.”

Favourable treatment for EU students would, of course, have to be preserved if the Scottish government held a second independence referendum (as it is contemplating doing in the wake of the Brexit vote, which Scottish voters opposed) and Scotland voted to break away from the UK in order to remain in the EU. In that scenario, it would be students from the remainder of the UK – who made up 13.1 per cent of total student enrolment at Scottish universities in 2014-15 – that faced having to pay international fees.

Variation in the impact of falling EU recruitment would be felt at a more granular level, too. For instance, data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that London-based universities and specialist institutions also tend to have particularly high proportions of EU students, and would therefore be more exposed to any deca. In 2014-15, non-UK EU nationals represented 18 per cent of full-time undergraduates and postgraduates at the London School of Economics, for instance, and 16 per cent at both Imperial College London and Soas, University of London.

In addition, EU students are particularly concentrated at taught postgraduate level, making up 11.6 per cent of this cohort, and there have been warnings that lower recruitment could force some courses to close. At 20 UK institutions, EU students made up more than one in five full-time taught postgraduates last year, their representation peaking at 29.8 per cent at the University of St Andrews and 25.5 per cent at the LSE.

Such is the uncertainty created by the Brexit vote that vice-chancellors’ lobbying efforts have so far been focused on the short term: seeking reassurances about the immigration status and loan eligibility of current students and those starting courses this autumn and next. But, even though the room for manoeuvre appears to be limited, the scale of what is at stake makes it likely that the political wrangling over the fate of EU students post-Brexit is only just beginning. Whatever arrangements are ultimately agreed upon, it will be important to phase in substantial changes gradually, according to Goodfellow. “One would want to see a transition period so returning students could continue on the same trajectory they were on and were not suddenly startled into something,” she says.

For von Prondzynski, however, the details of the new arrangements may be less important than the mood music surrounding them. In particular, he worries about the impression created by some of the pronouncements of vote Leave campaigners that immigrants “are not welcome in the UK”.

“This has affected the UK’s reputation across a number of countries, and not just in the EU,” he says. “We have encountered potential student applicants who are not sure whether they would be welcome in the UK. This is something that needs to be addressed urgently.”

New seams to mine: Is there gold in the postgraduate market?

With undergraduate fees tightly regulated and European Union recruitment at risk, where might universities be able to increase their income?

One opportunity suggested by The Complete University Guide’s survey of fees for the 2016-17 academic year is domestic recruitment to taught postgraduate courses.

The average fee for home taught postgraduates in 2016-17 is £6,486. This is a 9.6 per cent rise since 2015-16, and the figure is growing significantly more rapidly than most other fee categories. This is perhaps related to the fact that income-contingent loans of up to £10,000 are being introduced this autumn for home and EU master’s students, with institutions taking the opportunity to raise their fees towards that sum.

However, the fee levels remain significantly below the cost of running a master’s course, estimated to average £11,315 by a study published in 2014 by the Higher Education Council for England. Rosemary Deem, vice-principal for education at Royal Holloway, University of London and chair of the UK Council for Graduate Education, says that there is “increasing concern that master’s courses at English universities are being subsidised by undergraduate teaching” because the average cost of a master’s remains below the £9,000 undergraduate fee.

“Master’s courses are quite expensive to run, especially if they don’t have many students, because you need your best staff teaching their own research. People are starting to look at master’s fees and they are thinking that they need to put them up,” Deem says. And she suspects that the introduction of the loans “encourages people in institutions to think they can afford to put fees up by a bit more than they might otherwise have done”.

Looking behind the average rise, some institutions have increased their home postgraduate taught fees towards £10,000 at a particularly significant rate. For instance, the University of Bolton has increased its typical fee from £5,400 in 2015-16 to £9,000 in 2016-17, a rise of 66.7 per cent, while the University of Leicester imposed a 37.1 per cent rise, from £5,470 to £7,500.

Paul Wakeling, senior lecturer in the department of education at the University of York, says that the full impact of postgraduate loans is yet to emerge. “There are a few institutions that seem to have gone up much more towards the undergraduate fee, but in general, the average fee increase, while it is well beyond inflation, is not a leap straight up to £10,000. There is a lot of uncertainty at the moment, so that may lead people to hedge their bets a little,” he says.

Wakeling also highlights significant variation in domestic taught postgraduate fees, with the highest prices tending to be concentrated in the golden triangle of London, Oxford and Cambridge. “If people were following their financial interests, they would be going to some of those more provincial universities,” he says. “Fees at Birmingham, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle are quite a bit lower than in London.”

Where the numbers come from

Data are based on a survey conducted by The Complete University Guide. The survey results have been published annually since 2002, when Mike Reddin first presented them.

Institutions were asked to provide a typical fee, although some chose to provide a range. Figures are for guidance only. Fees for specific courses may vary from those shown. The averages exclude institutions that provided a range.

A dash (–) indicates that a figure was not supplied or that the university does not run the course. Universities providing no data have been omitted. A small number of figures have been added by Times Higher Education using figures from universities’ websites.

In Wales in 2016-17, Welsh-domiciled undergraduates will be charged £3,900 a year wherever they study in the UK. Undergraduates domiciled in Northern Ireland will pay £3,925 a year if they study there, but will pay up to £9,000 if they study elsewhere in the UK. Scottish undergraduates will pay no tuition fees in Scotland, but up to £9,000 elsewhere in the UK.

Fees Inflation: Costs for some courses are way up

Students starting courses at many universities this autumn will find themselves paying several thousand pounds more than their predecessors at the same institution did.

The Complete University Guide’s survey of fees for the 2016-17 academic year shows that Aberystwyth University is one of the institutions introducing significant increases in international fees across many of its courses. Non-European Union undergraduates and postgraduates at the Welsh institution will typically pay about £2,500 more in 2016-17 compared with 2015-16: a rise of between 20 and 25 per cent.

A spokeswoman says that the decision is the result of “increasing costs, recent significant investment in the student experience, and a benchmarking exercise undertaken across other UK universities”.

“As part of the fee increases, however, Aberystwyth has also increased the value and quantity of scholarships and bursaries available to international students on a country-by-country basis, as well as increased the amount and availability [of] hardship funds for all students once they are at Aberystwyth,” the spokeswoman adds.

Falmouth University is another institution introducing significant fee increases across much of its portfolio, lifting fees for domestic postgraduates and international undergraduates and postgraduates by between 20 and 25 per cent.

Some other institutions are imposing much larger increases in particular course areas. Proportionally, the largest recorded increase is at Bishop Grosseteste University, whose typical fee for an overseas student on a master’s course will more than double, from £6,000 to £12,500.

The University of Worcester is increasing the cost of an MBA for a home student by more than 80 per cent, from £4,900 to £9,000.

后记

Print headline: Paying the price