Browse the full list of the world's top 150 universities under 50 years old

When it comes to universities, students and academics alike tend to think that the older an institution is, the better it must be. But is that really true?

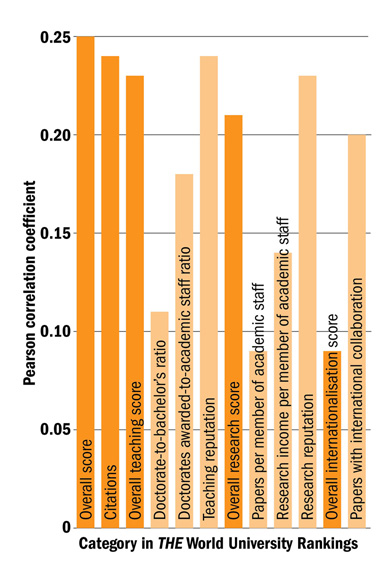

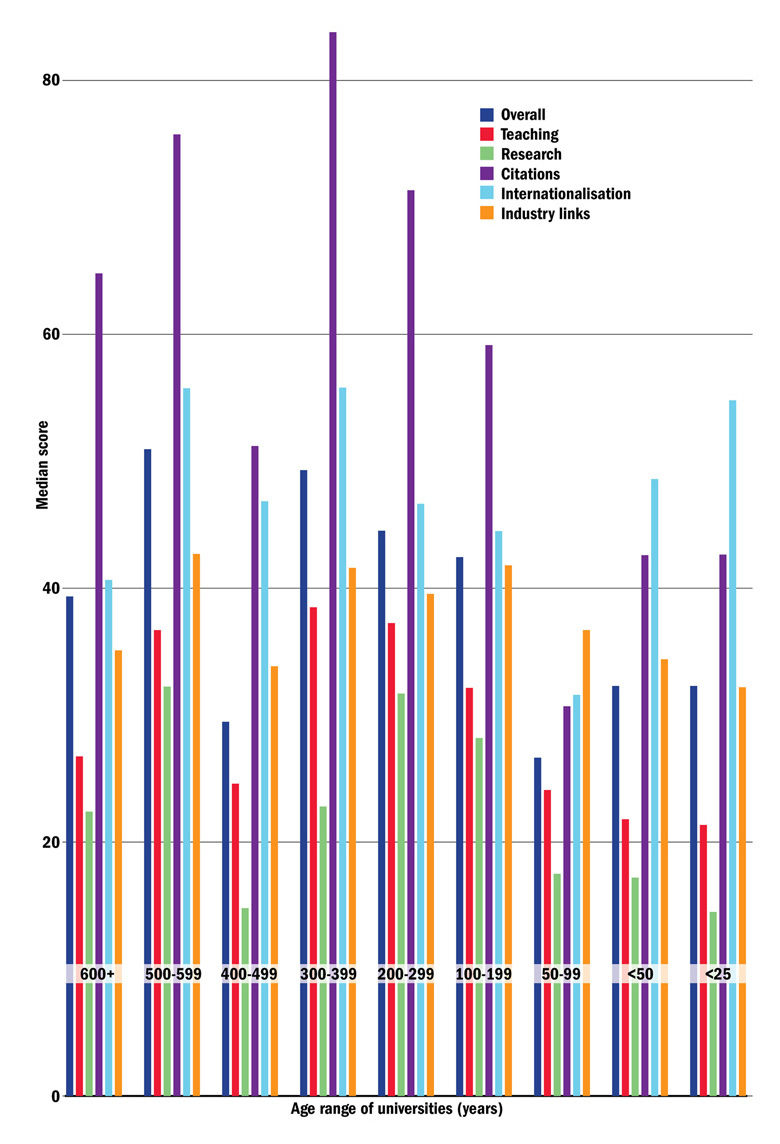

An analysis of the 800 institutions that feature in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2015-2016 suggests that it is – up to a point. Older universities do indeed tend to achieve a higher rank than newer institutions, and there is a weak correlation between the age of universities and both the citations they accrue and their performance on measures of teaching and research (especially their reputations in each). However, there is virtually no correlation between age and the other two main pillars of the rankings: industry links and internationalisation – except, in the latter case, a slight correlation between age and the proportion of internationally co-authored papers (see graphs, below).

Nor is it the case that the most ancient universities make up the most high-scoring demographic group. The 26 institutions in the rankings that are more than 600 years old include stellar performers such as the universities of Oxford (founded in 1096; second in the rankings) and Cambridge (1209; fourth), but also some relative underperformers such as Hungary’s University of Pécs (1367; in the 601-800 band).

In fact, it is the 20 universities between 500 and 600 years old that record the highest median overall score. These constitute a solid block of European powerhouses, among them Germany’s LMU Munich (founded in 1472; 29th), Belgium’s KU Leuven (1425; 35th) and Denmark’s University of Copenhagen (1479; joint 82nd).

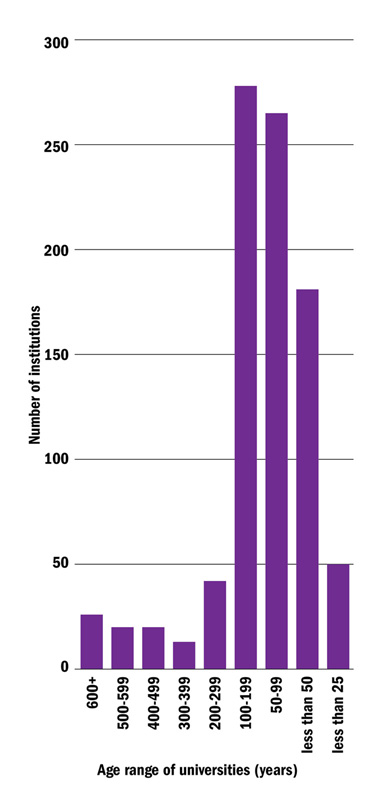

The age distribution of top 800 universities

Another notable period for university foundation – especially when judged on the number of citations their modern incarnations accrue – was the 17th century. That group of 13 includes European top-100 institutions the University of Amsterdam (founded in 1632; 58th in the rankings), Utrecht University (1636; 62nd), the University of Helsinki (1640; joint 76th) and Lund University (1666; joint 90th). But the key factor is that this was the era in which American universities began to be founded: most notably, Harvard University (1636; sixth) and Yale University (1701; 12th). As there are just 13 institutions in the rankings that date from this period, these two institutions significantly skew the figures upwards – particularly if you look at means rather than medians.

The biggest wave of university establishment began in the 19th century: 278 universities in THE’s top 800 were created between 1817 and 1916 – almost seven times the number (42) established in the preceding 100 years. According to Michael Shattock, visiting professor in higher education at the UCL Institute of Education, it was primarily economic worries that drove the Victorian-era expansion. For instance, “people had come back to Britain from the Great Exhibitions in Paris [held between 1855 and 1900] saying: ‘We cannot match them in technology unless we start investing in education and our industrial base.’”

The epoch was one of the most fruitful periods in history for university foundation in terms of quality as well as quantity. Although the 278 institutions from that era in the THE World University Rankings have a lower overall median score than those founded in the 15th, 17th and 18th centuries, they considerably outpace every subsequent epoch. Many of the 19th-century institutions that perform particularly strongly are US state universities, often known as “land grant universities” after the vast swathes of land gifted to them by the 1862 Morrill Act, which was enacted shortly after the end of America’s Civil War, Shattock explains. That legacy guaranteed a degree of financial security and autonomy for the institutions – especially the University of Texas, whose 2 million acres of arid farmland turned out to be situated atop a massive oil and gas field that has yielded up to $1 billion (£705 million) annually in recent years.

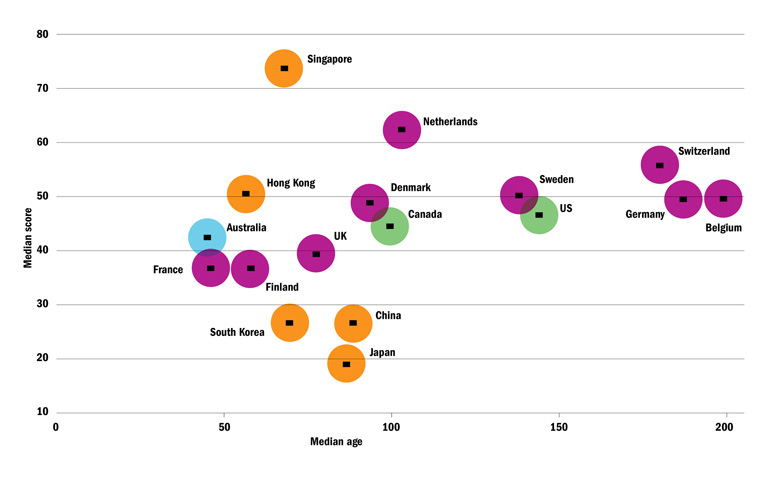

Median age and score of universities, by country

Note: Only countries with a university in the top 100 are listed, but data cover the top 800

“People often think about Princeton and Harvard when they think about US higher education, but it is really a state system, particularly outside the Northeast,” says Roger Brown, emeritus professor in higher education policy at Liverpool Hope University. The formation and support of successful state universities is “the real triumph of US higher education”, he says, and one that offers lessons for the many modern-day governments keen on establishing world-class research universities. Like the plate-glass universities established in the UK in the 1960s, US state universities were the result of “government action and continued support – but the state then took a back seat in steering them”.

Political consensus that public spending was a good thing also helped to drive the creation of new universities across Europe in the early to mid-20th century, says Robert Anderson, professor emeritus in history at the University of Edinburgh, who has written extensively about the history of British higher education. Some 265 institutions in our rankings were created between 1917 and 1966, although, interestingly, their median overall score is lower than those of every other age range examined by our analysis – including universities created even more recently.

Also crucial in spurring the creation of new universities in the 20th century, Anderson adds, was the massive increase in student numbers resulting from the post-war baby boom, coupled with educational reforms that kept more students in school for longer.

Indeed, this expanded pool of students is the most significant factor regarding epochs that produce outstanding universities, says Tyler Cowen, the Holbert C. Harris chair of economics at George Mason University, in Virginia, US. It explains, for instance, much of the 20th-century rise of US West Coast universities such as Stanford University (founded in 1891 and third in the THE World University Rankings), the California Institute of Technology (1891; first) and the various University of California campuses (the first of which, Berkeley, was founded in 1868 and is ranked 13th).

Singapore is another good example of how growing numbers of students, high levels of state investment and a commitment to academic autonomy can produce stunning results, adds Cowen, who has acted as an adviser to the city state.

“Everyone knows in Singapore that the best professors and students will be rewarded in its honest environment,” he says, adding that “promises to respect autonomy of the schools are very much believed”.

Correlation between university age and performance

Notes: A correlation coefficient of 1 represents a perfect correlation; −1 represents a perfect inverse correlation; 0 indicates no correlation. Only statistically significant correlations are shown

Indeed, Singapore shines particularly brightly in the World University Rankings. The fact that its two representatives – the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University – are both highly ranked (26th and 55th, respectively) makes it the top nation in terms of the median scores of its ranked institutions for teaching, research and international links, and second for citations and industry links. That feat is achieved despite both the NUS and Nanyang having been founded relatively recently (in 1905 and 1991, respectively): youth is usually seen as an impediment in rankings because of the weight they give to surveys of academic esteem, which is often considered to accrue most naturally to the oldest universities. The Singaporean institutions’ median age of 68 is less than half that of ranked universities from the US (144 years), and far younger than those from European countries such as Germany (187 years), Switzerland (180 years) and the Netherlands (103 years).

Some university leaders have suggested that a relative lack of history is, in other ways, a positive factor because it allows institutions to fashion their own identity as they wish rather than having it determined by centuries-old traditions. This point was made by Lisa Anderson, who recently stepped down as president of the American University in Cairo, at the Times Higher Education MENA Universities Summit in the United Arab Emirates in February. Campuses of many historic universities are “as much a burden as an advantage” given their maintenance costs, she argued, while newer institutions could be founded with modern technology and teaching methods at their heart.

Renee Hindmarsh, executive director of the Australian Technology Network of Universities, which represents five technology-focused institutions mostly founded in the 1980s, says that newer universities in her country are indeed doing things differently, offering new forms of teaching and research that produce more workforce-ready graduates.

“They tend to be more nimble and responsive,” she says. “The ATN universities are all heavily engaged with industry to deliver world-class, real-world research. [They] were founded with translation [of ideas] to market and solution-provision at the heart of [their] activities. Older universities are following this lead, but younger ones, ironically, have been living it for longer.”

Performance by age group

However, critics note that aspirations to be distinctive can often wither in the push to climb university league tables. “History is littered with examples of innovative institutions trying to offer something different in their early stages, which become fairly conventional as they seek to join the club,” says Brown.

This aspiration often entails ambitious universities in emerging economies importing as research leaders big hitters from established research powers in the US and Europe, who then seek to replicate a version of their old university in a different context (see 'Missteps on the steppe: Nazarbayev University' box, below). However, the perception that ranking success relies on merely implementing a tried-and-tested formula using huge financial resources ignores much of the innovation and creativity that research leaders from outside help to instil in the up-and-coming institutions, says Stephen Smith, who was vice-president of research at Nanyang from 2011 to 2013. “The greatest institutions are those that create new ideas,” says Smith, who was in post at the beginning of the Singaporean tiger’s remarkable 119-place climb in the rankings since 2011, and has also held senior roles at Cambridge and at Imperial College London. But “you need to bring in people who know how to work in this very sophisticated knowledge set-up that creates ideas”, he adds. Having top US and European academics who are able to challenge accepted orthodoxies and processes is part of the reason for Nanyang’s success, he believes.

“When you are in a Confucian social context, it can be hard for researchers to challenge more senior colleagues or those in power. But I began to see substantial change in younger Singaporean and Chinese scientists in my time there. They were empowered and really began to understand that ideas matter, not status.” These people, he adds, will be the university leaders of the future in Singapore.

So although age may still be a factor in the global pecking order, the rise of modern institutions such as Nanyang make clear that university leaders cannot take their positions for granted, whatever their institution’s foundation date may be.

Note: Data are drawn from the World University Rankings 2015-16 © THE data@timeshighereducation.com.

The learning world: A history of global universities

The University of al-Qarawiyyin in Morocco, founded in 859, is often billed as the oldest continually operating degree-awarding institution in the world. And India’s University of Taxila or University of Nalanda, both of which were founded several centuries BC, are often cited as the first universities ever to be established.

But the first institutions to fit the modern definition of a university were the universities of Bologna, Paris and Oxford, founded around 1100 to teach rhetoric, philosophy, theology, law and medicine. What distinguished them from their peers, from around 1200, was their status: rather than congeries of independent teachers, they were recognised by church and state as corporations. As such, they were independent, privileged institutions with the power to defend their interests in court, to police their members and to bestow degrees.

The new model proved seductive. By 1400, the number of schools classed as universities had risen to more than 30. Two and a half centuries later, this figure had grown to 150. Much of the impetus for the further expansion came from a need for well-trained lawyers and administrators as the decentralised feudal state gave way to its more powerful early modern successor. From 1560, the expansion was also fuelled by the Reformation: the competing confessions placed a novel premium on a well-educated clergy. By 1750, even the smallest state had at least one university: France had 25. England, given its size, was peculiar in still having only two.

Between 1800 and 1945, the university map on the European continent hardly expanded, despite a threefold growth in population and the increasing wealth brought by industrialisation. In the Napoleonic era, several German and Spanish universities were even abolished; while in France, in a development that would last until the 1890s, the universities were replaced by a system of subject or faculty schools, directly under state control. Only in Russia and the British Isles was there significant expansion of the European system before the Second World War. The stagnation had two principal causes. Few universities in the 18th century had more than 1,000 students, and many had only 100 or so: they had no difficulty taking in extra numbers after 1800. Second, the universities in the main continued to teach a traditional curriculum and to train people for the old professions and for secondary-school teaching: outside the Soviet Union, they played little role in training the new industrial, commercial, administrative and technocratic elites. In 1940, only 1 to 2 per cent of 18-year-olds in Western Europe went to university. If the new elites sought an institutionalised education, they had their own schools, notably the German polytechnics and the French grandes écoles.

But, outside Europe, many universities were founded in the 100 years before 1945, especially in the British dominions, India, Japan and North America. There were already universities and colleges of higher learning in Spanish and British America long before independence, but in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the number in the US exploded with the establishment of the state universities. These, too, were very different institutions from the universities founded under European influence elsewhere, for they developed degree courses in practical as well as theoretical subjects and encouraged a broad social intake.

After 1945, the US model was copied in both the developed and the developing world, and the traditional distinction between universities and technical and commercial schools was gradually eroded. Governments accepted the need to increase the number of graduates for social and economic reasons and were happy for universities to extend their curricula: successful states required a well-educated workforce. They also accepted that universities should be research as well as teaching institutions, a German idea taken up in the US but one that hitherto had had limited purchase in most European universities.

The number of universities mushroomed on the back of states’ willingness to fund expansion, especially in science and engineering. The advent of the new technology in the 1990s only enhanced that willingness. By 2000, participation rates of 18-year-olds in higher education in Western Europe had increased to 40 to 50 per cent. In 1940, there were 18 universities in the UK; today there are 165. In the world, the number has now reached 17,000 and there are 153 million students.

Laurence Brockliss is professor of early modern French history at the University of Oxford. His most recent book, The University of Oxford: A History, is published by Oxford University Press this month.

Missteps on the steppe: Nazarbayev University

More and more nations want to try to create at least one or two globally ranked institutions of their own. Kazakhstan is one of the most recent nations to join the race.

Nazarbayev University is an English-speaking institution founded in 2010 on a brand-new, Japanese-designed campus in the country’s brand-new capital, Astana. According to its website, it “aims to become the first research and world-class university in Kazakhstan”. The list of globally prominent universities advising its schools includes University College London, the University of Cambridge and Carnegie Mellon University.

Unlike other publicly funded higher education institutions in Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev is not under the umbrella of the Ministry of Education and Science: a symbolic break from the country’s Soviet history, with its Stalinist approach to education. However, apart from the institution’s president, Japanese economist Shigeo Katsu, the institution’s “supreme board of trustees” consists entirely of political figures. It is chaired by the country’s president himself, Nursultan Nazarbayev, after whom the institution is named, and also includes the Kazakh prime minister, the deputy prime minister and the ministers of defence and education (the latter, Aslan Sarinzhipov, is also an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education).

Despite an aggressive international hiring campaign, complete with promotional videos on YouTube, most of the recruits so far have been at the junior faculty level, and there still appear to be examples of locally recruited faculty with old academic credentials. The School of Medicine promises a US-style curriculum, but very few of the faculty recruited so far hold US medical degrees. Given the continuing devaluation of Kazakhstan’s currency, driven by the collapse in the price of the commodities that are the country’s main export, it is going to get only harder to offer international staff competitive salaries.

On social networks, you can already read claims about the depreciation in the value of salaries, as well as salaries lower than promised and other alleged contract violations. There are also complaints about the isolation of the location and worries about the extent to which free speech is tolerated.

President Nazarbayev has no choice but to step in and take a closer look at his brainchild. Better, clearer rules around hiring and contracts are evidently required, as is a greater effort to diversify the student body and to recruit prominent scholars. Until Nazarbayev University gains international visibility through scholarly publications rather than advertisements, it has no chance of making an impact on global rankings.

Ararat L. Osipian holds a PhD in higher education policy from Peabody College at Vanderbilt University, US. He served in a collaborative international project between Vanderbilt and three universities in Kazakhstan, funded by the US Department of State.

后记

Print headline: The age of ascent