Is there a time in human history that deserves to be described as the “Age of Genius”? And where should we look for the birth of the “Modern Mind”?

Over the past few decades, intellectual history has struggled to free itself from two tempting – and potentially misleading – postures that dominated the field in the past. The first of these is the stress on meaningful discontinuities: turning points that are taken to mark the beginning of a radically new age in human thought or the terminal decline of another. The second is the tendency to imagine the existence of direct links between historical events and intellectual developments. Both postures are convenient supports to the building of articulated narratives. They are also, at least intuitively, plausible: novel ways of thinking do emerge in human cultures, and it is reasonable to assume that wars, revolutions and other major upheavals might be connected somehow to radical changes in collective mentalities. At the same time, these connections are mere rhetorical devices, as it is impossible in practice to establish direct causal relationships between events, actions and ideas. Accordingly, historians have learned to use them with great caution, focusing as far as possible on very specific, well-defined contexts.

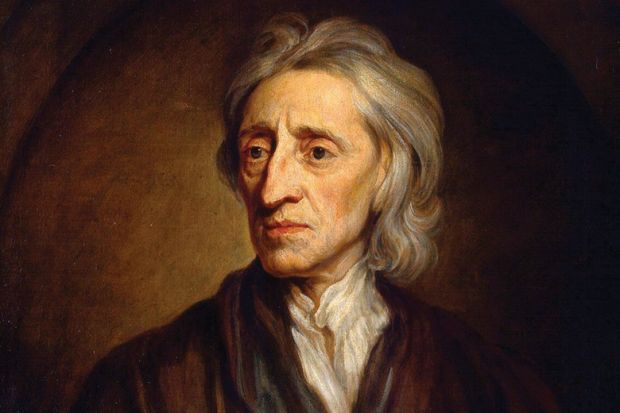

Apparently, these prudential concerns have no place in A. C. Grayling’s work. In this book he offers a sweeping and vivid, if disjointed, tableau of the 17th century generally considered, roaming freely from the Thirty Years War and the rivalry among European powers, to various scientific and philosophical developments; from the events of the English Revolution, to the political views of Locke (pictured above) and Hobbes. The central focus of this spirited tour de force is the transition from a society dominated by superstition and magic – but also by the power of the established Church – to one in which the modern mind finally comes into its own, thanks to a new generation of pioneering philosophers and scientists. Because of this transition, not only is “the seventeenth century…a very special period in human history”, Grayling argues, “It is the epoch in the history of the human mind.”

This epiphany of the modern intellect runs parallel to another development, this time political, namely the abrupt passage from a context in which regicide was viewed as a sacrilege – as illustrated by Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the beginning of the century – to one in which King Charles I could be put to death by Parliament less than 50 years later. It is clear at this point that the “Age of Genius” is an essentially English affair: indeed, we are told that just when England leaped forward towards modernity, France was moving backwards, towards despotism.

In this book’s conclusion, Grayling is forced to admit that even today, in many parts of the world, the pre-17th-century mind is still “actively in control of people’s lives”, a phenomenon he does not really attempt to explain. It is natural for historians to be guided by feelings of sympathy for their subject, but here the claim to the uniqueness and superiority of intellectual developments in the 17th century in England stretches too far on very thin ground. Readers may enjoy, and possibly learn something from, Grayling’s book. But philosophy cannot play, as he wishes, “an active and useful role” in society if we gloss over its secular heritage of complexity, diversity and contrast.

Biancamaria Fontana is professor of the history of political ideas, University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By A. C. Grayling

Bloomsbury, 368pp, £25.00 and £17.99 (e-book)

ISBN 9780747599425 and 9781408843291 (e-book)

Published 10 March 2016