From where I sit, I can hear the clanking of old-fashioned brass bells, hung around the necks of a herd of ponies grazing contentedly in the field next door, while behind them the vast bulk of the Pyrenees rises up.

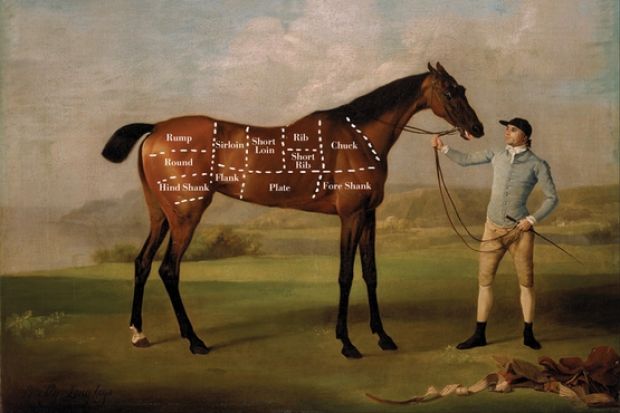

These are the short, thick-set little creatures with big dark eyes that, like all the equine breed, seem to gaze at you with profoundly philosophical sadness. And now, it turns out, these are also the kinds of animals that turn up in our lasagne. The ponies in this field are for meat. It was not Findus UK that produced the controversial ready-meals - but its French supplier in Metz.

While horsemeat is a scandal across La Manche, it is still an everyday affair here, an approved part of Gallic cuisine, along with stuffed goose livers, snails and frogs’ legs. But somehow, ponies (and horses) seem to me to be different. These are animals quintessentially for companionship. As George Bernard Shaw put it: “Animals are my friends, and I don’t eat my friends.”

That’s an ethical stance, and one I examined in an introduction to ethics I wrote some years ago, long before I moved to France. I thought then, and still do now, that ethics is created out of the myriad little decisions of everyday life, be they how we treat colleagues or family, how we spend our money or what we choose to eat. If relations in the workplace and family are open, consensual and guided by agreed principles, the state will follow, not vice versa. And if we turn our eyes away from the meat industry, as Plutarch says, then the same cold utilitarian ethics will be applied to human lives, too.

But back to eating horsemeat. The French used to do a lot more of this; indeed, they claim (however implausibly) to have “invented it”. Standard school textbooks explain how, in the early 19th century, “hippophagy suffered from an execrable image”. As Sylvain Leteux, a French sociologist, says, it was a shameful food, associated with the dregs of society, with poverty, with piles of rubbish in the streets.

And then Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, a zoologist and professor at the Natural History Museum, and Émile Decroix, a veterinarian and member of the newly created Humane Society, saw in the horse a way to feed the inexorably increasing working and urban populations of industrialising France with a “very healthy meat”, as well as a way to encourage owners to take a little more care of their beasts and not leave them to die in the streets under angry blows (the sight of which, famously, caused even arch anti-sentimentalist Friedrich Nietzsche to ethical action).

By the 1970s, the annual appetite for horsemeat in France was almost 2kg per person, although now it is just an occasional treat (at up to €23, or about £20, a kilo). French gourmets say that it can be chewed easily and leaves a sweet taste “at the bottom of the mouth”.

But there is a problem. Jean-Pierre Digard, ethnologist at the CNRS (the National Centre for Scientific Research), says: “The horse, once a symbol of all things military, aristocratic, masculine - not to say macho, has instead played an unconscious part in the feminisation of society.” When ponies were imported in the 1970s to carry children, horseback riding was feminised. Today, riders are “no longer interested in using and dominating the horse but rather in mothering, brushing and feeding”, he adds. Alongside the rabbit, the horse became a pet. And parents cannot eat the family pets.

Not knowingly, anyway.