Source: Getty

When an illustrious journalist addressed undergraduates at a London university, he inadvertently revealed some sensitive information about his publication’s operations. He was not too worried about his slip, though; the host of the event had already requested that delegates keep the contents of the presentation private.

Unfortunately for him, one student - himself an aspiring journalist - chose to overlook the ban on external communication. Unbeknown to the person giving the presentation, the undergraduate had been “live tweeting” throughout the talk, posting excerpts on the social networking site Twitter for all to see. Before the speaker’s lecture had even concluded, a news story appeared on the website of a national newspaper, quoting the speaker and the sensitive information he had divulged.

It emerged that the student’s tweets had been spotted on Twitter by a number of national journalists, and that one of them could not resist including this nugget of fresh information in a story that quickly went live via the internet.

Making matters worse, the information quoted had been taken out of context and the presentation of the figures was inaccurate.

A few hasty phone calls later and the news story was altered; the student who broke the curfew was disciplined; and the guest speaker made his way home, feeling a little out of sorts.

This sequence of events, which unfolded at Goldsmiths, University of London a few years ago, highlights some of the problems that can emerge when conference delegates take to Twitter to disseminate the contents of the event they attend. First, a request for confidentiality was ignored; second, someone outside the event opted to use information that had been provided by a third party; and third, the information published was inaccurate - yet this was not detected before it had spread across social networks and was published by a respected newspaper.

Live tweeting at academic conferences and at talks on campus is now commonplace - but should there be limits? Earlier this year, a heated debate broke out on (where else?) Twitter about the ethics of tweeting content from presentations of unpublished research. Some academics argued that there could be serious repercussions should information intended to be kept within four walls make its way into the public domain. Others claimed that any public presentation of information was fair game for the discerning tweeter.

The discussion - christened #Twittergate - unearthed many stories of scholars presenting unpublished ideas to an audience of peers only to find content from their work appearing on Twitter as they spoke. Some were concerned that rival researchers might incorporate the information into their own findings. Others said that such concerns were paranoid, and that discussing research on Twitter was no different from talking about it over a cup of tea after a talk had concluded.

Erin Templeton, the Anne Morrison Chapman distinguished professor of international study and associate professor of English at Converse College in South Carolina, took part in the debate, and she advocates a cautious approach. It is presumptuous to assume that it is acceptable to share other people’s work without asking them first, she argues.

“It is important to recognise that a conference presentation is not necessarily a public presentation,” she says. “It requires delegates to pay entry fees and wear name badges to get to certain places. It is not just open to anyone who wants to be there.”

However, Tressie McMillan Cottom, a doctoral student in educational studies at Emory University in Georgia, sees live tweeting as a route around the attendance fees charged by many conferences. These are a barrier not only for the general public but also “for students and adjunct/contingent academic labourers”, she argues.

“I consider tweeting at conferences a means of sharing the privilege of attending with the public - who, directly and indirectly, make the work we do possible - and the colleagues who cannot attend,” she explains.

Although she would honour any request from a speaker who wishes to keep a presentation private, McMillan Cottom admits to having “serious issues” with scholars who make such a demand.

“I caution them that they can control only what happens in that room, in that moment. As was true before the advent of social media, speakers cannot control how an audience receives and shares their impressions of a talk… I may not tweet during the talk, but I think discussing my impressions of a talk (afterwards) is as much my domain as a tweet ban is the domain of a speaker.”

She believes that many of the academics who decide to discourage live tweeting do so because this makes the discourse around their presentation invisible to them. “For some, that is comforting. I’d argue it is a false comfort.”

Bonnie Stewart, a PhD student researching developments in online learning at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown, Canada, also takes a more relaxed approach to Twitter. “To me, a tweet ban is the equivalent of asking people not to continue the conversation over the water cooler,” she says.

While she accepts that some academic areas may be more likely than others to contain sensitive information, she says that those who are “concerned that someone will steal your great idea, for instance, and pass it off as their own, may be misunderstanding Twitter’s operations and etiquette”.

“If I give a talk about how X causes cyberbullying, for instance, and the audience live tweets that, I now have a public record tying my name and a traceable Twitter ID to the idea that X causes cyberbullying, even if my paper on the subject is still stuck in peer review,” she explains.

But Templeton warns that reproducing the content of conference and seminar presentations online runs the risk of damaging the value of academic events, which have traditionally provided a safe space for sharing and discussing developing ideas and early research findings with colleagues - to the point that audiences could be deprived of presentations on groundbreaking, albeit unfinished, research.

“There’s a worry that we might transform the conference space into somewhere where we present only finished work, which is a shame for the academy because there is a lot of value in being able to present work in progress as work in progress.”

Discussions around tweet etiquette often focus on a perceived generational split and the theory that younger academics are keen to explore new media channels while older members of the academy might be more sceptical - or simply more set in their ways.

“The whole issue of live tweeting academic conferences is one of the areas where some of the assumptions of the traditional academy come into conflict with new media possibilities and emergent practices,” argues Stewart, pointing to “increasingly divergent understandings of what counts as legitimate practice for academics”.

For example, is it polite for an audience of academics to sit, heads buried in smartphones, laptops and tablets, committing every thought of the on-stage presenter to internet posterity without even affording them eye contact? Is it acceptable to conduct a very public, tangential conversation about one of the themes of a conference talk with a former colleague who is not even physically present?

“Some speakers, as well as other participants, might find it distracting when audience members are on their phones, tablets or laptops when a paper is being read. This might look like audience disengagement or partial inattention, but for some people tweeting is how they take notes and later archive the presentation and make it available to others,” says Simone Browne, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Texas at Austin.

But Templeton has some sympathy for those who are less welcoming of new technologies and who would rather their talks remain within traditional boundaries.

“I gave a paper at the [2011] Modern Language Association conference, and it was really disconcerting to address a room with all those smartphones and computers open, with nobody looking up,” she says.

“We are at an important transitional moment between print and online. It’s important to respect people who aren’t comfortable with live tweeting - it may be an issue of intellectual property, or just that they are self-conscious and personally uncomfortable with it. That is understandable and we should respect it.”

Whether you are a fan of social media or not, the next time you present a paper there will almost certainly be someone in the room who wants to share your thoughts online.

Some conferences now outlaw the practice of live tweeting, while in other cases it is down to individual speakers to request that their presentation is kept inside the room. Enforcing such restrictions, however, is never easy.

At the American Studies Association conference, held last month in Puerto Rico, the programme guidelines stated: “The papers and commentaries presented during this meeting are intended solely for the hearing of those present and should not be tape-recorded, copied, or otherwise reproduced without the consent of the authors.”

Browne, who was at the conference, was unimpressed by the instruction. “What does it say about the politics and practices of access?” she asks. Despite the guidelines, “there was a Twitter showdown early on…and the guidelines didn’t stop people from live tweeting and blogging about the conference panels.”

Whatever the rights and wrongs, it seems that conference organisers can no longer limit the potential for the information shared within presentations to be disseminated more widely simply by excluding the press, and today’s academics should be aware that content from even the most intimate of events might be broadcast online within seconds.

“Previously, [academics] would have dealt completely differently with a room full of journalists than they would with a group of, say, healthcare professionals,” says Chris Brauer, founder and co-director of Goldsmiths’ Centre for Creative and Social Technologies. “But this is no longer the case. Even if there are only 20 people in the room, if there are one or two prolific tweeters, the discussion will be followed far more widely.”

Behind you! Twitter pranks and pragmatism

Do you ever get the feeling, when presenting a paper or delivering a lecture to weary undergraduates continually checking their iPhones, that some people in the room might be surreptitiously sharing remarks about you?

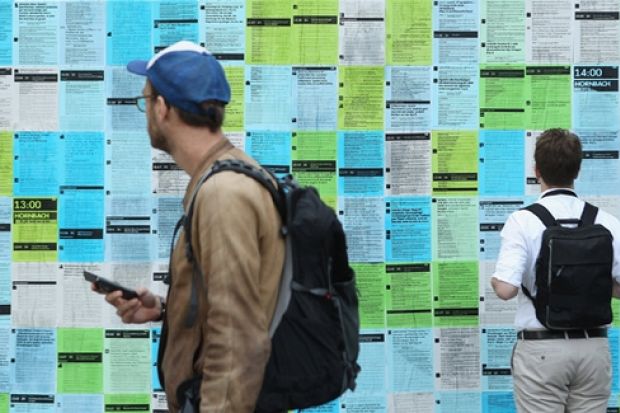

Conferences increasingly allow delegates to do just that and “talk” behind a speaker’s back thanks to the use of Twitter walls - screens displaying tweets that are relevant to a particular session in real time.

In theory, this allows delegates to discuss the presentation they are watching while making it possible for others (Twitter users or not) to “listen” in. These walls usually operate by detecting and automatically displaying tweets carrying a particular phrase.

However, Twitter walls are not always used for their intended purpose, as Alice Bell, research fellow in science policy research at the University of Sussex, explains.

“At one event, a speech about a relatively dry topic was being discussed - journal referencing or something like that. People were almost falling asleep, but there was a Twitter wall in place on the stage.”

Delegates decided to liven things up a bit.

“A cricket match was going on at the same time, so people started tweeting the cricket scores but adding the name of the conference so that it came up on the screen. It was very rude.”

“At another conference session that I was chairing, there was a Twitter wall that really backfired,” Bell continues.

“At one point someone was making a joke on Twitter that was slightly rude - it related to something sexual about sexual politics. The audience started laughing because of what was on the wall above the presenter’s head, and although she tried to take it in her stride, it did knock her back a bit. It made her stumble.”

Chris Brauer, founder and co-director of the Centre for Creative and Social Technologies at Goldsmiths, University of London, has experimented with Twitter walls during his lectures, and he likes the instant feedback. If students do not understand something he says, for example, this can be instantly communicated and he can go back and explain.

“I stopped getting annoyed at people using laptops and phones in my lectures a long time ago,” he says.

Despite issuing guidelines, Brauer says there are still occasional incidents of misuse.

“Everybody experiences negative tweets sometimes. If it is up on a massive screen behind you, it can be embarrassing and difficult to deal with, but I try to treat it like any other question.”

Lecturers, he says, “have to come to terms with the idea of losing control in the world of interactive media. You are fighting a losing battle if you want to control it - you have to hope it leads to a constructive debate.”