At the turn of the 20th century, Frederick Taylor invented “scientific management”. His time and motion studies and Henry Ford’s production lines led to alienated, monotonous working lives, absenteeism and industrial action. Taylor’s excesses were counterpoised by Elton Mayo, a Harvard University professor, psychologist and founder of the “human relations” school who strove to repersonalise management by coaching and counselling recalcitrant workers. Today’s teamwork-based production and continuous improvement structures owe much to Mayo. Such, says Gerard Hanlon, is the dominant narrative of management theory, and he is having none of it.

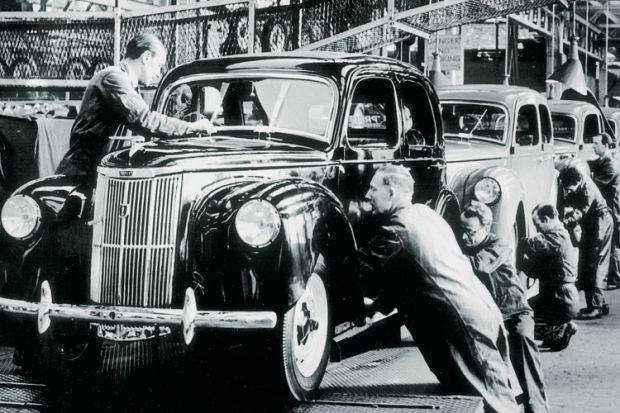

For Hanlon, Taylor and Mayo are members of a longer, darker tradition dedicated to extracting value from labour, a story he tells through an engaging synthetic history of labour in 19th-century America. He charts the move from the patriarchal, family-based small farm to the rise of the cash wage economy as cities grew and available land shrank; the war on craftsmanship through the division of labour and the growth of the factory; pressure on labour as women and children entered the workforce, and yet more pressure as Irish immigrants flooded into the US. The shrinking of wages and the near compulsion of labour was accompanied by a moral crusade against the sinful habits of the working classes, seeking to create a moral subject that valued ambition and industry as a route to social and economic self-improvement.

Into this milieu stepped Taylor, his mission to extract knowledge from skilled workers and hand it to management, and to increase labour output to an almost unbearable level. The result was the very industrial action and worker resistance that Mayo tackled: what Taylor did for the body, Mayo did for the soul. Hanlon argues – with good grounds – that Mayo’s psychoanalytic methods were yet another form of the disciplinary “confessional” identified by Michel Foucault. Mayo’s workers were coached towards a productive subjectivity where capital could benefit not just from their physical labour but also from their values and aspirations, which Hanlon terms (after Marx) the “general intellect”. In this light, Mayo seems far more culpable than Taylor, who was at least honest about what he sought to achieve. Taylor regarded his labourers as brutes and treated them accordingly; Mayo’s elitist psychoanalytics cast the working class as an irrational, riotous mob, whose very existence threatened civilisation and whom management had a duty to tame.

Hanlon’s polarised divide between capital and labour is sometimes too blunt for the subtleties of his historical account. On the one hand, his crucial point – that during the 20th century management somehow emerges as the most valuable occupation in the factory, is important and well made. On the other, using management as a synecdoche for capital means that we are unable to account for the pressures placed on managers themselves. Hanlon is talking about two kinds of management at once: everyday white-collar work in factories and offices, and a band of elite business-school academics.

In fact, the former is more interesting. Taylor’s and Mayo’s work has become the model for 20th-century labour relations, and the revelation that management gurus are the handmaidens of capital is perhaps not too much of a shock. The growing “expropriation” of the “general intellect” through knowledge work and social media, on the other hand, means that there are many more stories about management and capital in the 21st century needing to be told.

Philip Roscoe is reader in management, University of St Andrews.

The Dark Side of Management: A Secret History of Management Theory

By Gerard Hanlon

Routledge, 228pp, £75.00 and £19.99

ISBN 9781138801899 and 1905

Published 7 August 2015

后记

Print headline: How the takers took over from the makers