The Chair – the Netflix original series set in the English department of a fictional US Ivy League university – caused quite the storm in academic circles last year.

As noted by Karen Tongsen, chair of gender and sexuality studies at the University of Southern California, “television and film have failed [spectacularly] to get even the major details of our profession right” over the years. But here, finally, was a show that promised to give us a genuine insight into the world of academics – and, particularly significantly, depicted a woman of colour (Sandra Oh) as departmental chair. However low our expectations, you bet we’d all be tuning in.

When the series finally dropped in August, however, many academic reviewers considered their low expectations largely confirmed. Critiques questioned the series’ verisimilitude, politics and, perhaps most importantly, the centring of the chair’s life on the drama caused by her almost irredeemably narcissistic love interest and colleague. We seem unlikely to see a second season.

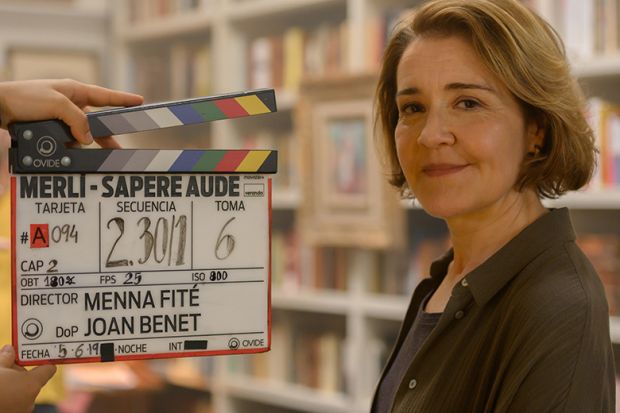

But for those who still feel like giving TV one last chance to get academia right, there is another show in town – even if anglophone audiences would be lucky to have realised. Originally released in 2019, the Catalan- and Castellan-language show Merlí: Sapere Aude has been available on Netflix since the start of the year, and was somehow thrown up by the platform’s inscrutable algorithm in my “top picks” list.

Set at the University of Barcelona, the show ostensibly focusses on the story of Pol Rubio, a first-year student of philosophy, as he comes to terms with his sexuality and explores university life. However, the ensemble nature of the show pushes beyond that framing, also exploring the lives of Pol’s friends and fellow students – rich, poor; Spanish, Argentinian, French, American; straight, gay, bi – as well as those of his professors.

The series isn’t for the small-minded. The sine qua non (or at least baseline expectation) of Spanish-language shows marketed to anglophone audiences has become a certain raciness, or fleshiness, and Merlí dutifully conforms. The first episode opens with a slow panning shot of Pol’s bottom as he showers, before masturbating: as La Vanguardia’s critic Pere Solà Gimferrer observed, the show’s creator “could hardly have been clearer if he had written ‘you’re welcome’ on the screen”. (And on the subject of self-pleasure, after an extraordinary tripartite scene in episode four, I will never be able to look at a highlighter in quite the same way again).

All this said, the show is substantially less nudity- and sex-heavy than another, more heavily marketed Netflix property, Elite, set in an expensive Madrid high school – and less melodramatic to boot. The show’s craft, effect and affect lie instead in its truly compelling interlacing of the personal, political and philosophical.

Señora Bolaño’s ethics classes are a hoot: hedonists on the left; Kantians on the right; go! Within the first few minutes of the opening episode, students are asked by an adjunct professor, Montoliu, to confront “the famed degree [philosophy] with no prospects” and the “shame that associate professors [adjuncts] only get paid 500 euros” at one of the highest-ranked universities in the world. A third academic laments that academic planning requires the “McDonaldisation of culture”.

Bolaño tests the attitude of her new students towards society’s shifting morals (and invokes the hot-button issue of free speech) through a deliberately provocative set of “jokes” and a description of a university janitor as “un negro pobre” (adding “the only thing we have to do so we don’t get fucked is to be born male, white, rich and heterosexual”).

Are we meant to loathe or love Bolaño? I’m of the school of thought that allows for multiple, individualised and undetermined responses to a character – indeed, to a show. For all her self-professed adherence to the ancien régime when it comes to proposals to diversify assessment methods or take attendance into account when awarding grades, we are invited into the pathos of a woman who struggles with loneliness, separation from her husband, alcoholism, and being mother to an adult daughter with Down syndrome who is determined to confiscate her mother’s alcohol (a brilliant performance by Gloria Ramos).

Bolaño’s friendship with Montoliu is also fraught by her anxiety to remain of interest to her students despite the greater relatability of her younger colleague – who attempts to navigate her office-mate and erstwhile supervisor’s self-destruction via a thermos flask filled with vodka.

In short, Merlí: Sapere Aude offers glimpses into academic life that are truly compelling and, at times, disturbing. Unlike The Chair, the cast is emphatically white – there’s no getting away from that. But while it fails to break new representational ground, it does explore widely, and the juxtaposition of the optimistic, hedonistic, sexually liberated narrative of the students with that of the struggling catedrática is riveting.

From Bolaño’s personal and professional miseries to the vibrant scenes of a student strike against fees and marketisation, what could be more topical for anglophone academic audiences?

David Lunn teaches at SOAS University of London, where he is also UCU branch secretary.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login